SOMALIA 1993

Somalia's agony appeared to last a shorter time than Mozambique's, although that may have only been an impression created by lack of media interest after the UN forces left.

Within months of my earlier visit with Bob Hawke, I was back in Somalia with the delegation of World Vision leaders who visited Mozambique in the last chapter.

The Somalia experience focussed some of the issues in emergency relief. There is a way to deliver food aid without it being stolen. There is a way of preserving local community power structures. There is a way to help people in crisis while still keeping an eye on their long term rehabilitation, most of which will rely on their own capability. Agencies have to deliver their own magnificent and impressive capability, while not destroying the capability of the people themselves.

Travelling Companions

The flight to Lilongwe from Quelimane took about two-and-a-half hours and we had plenty of time to connect with our scheduled Kenyan Airways flight. The process was rather complicated. They wanted to process us through immigration, so we entered Malawi just so we could leave again (and pay the airport tax of US$20).

We queued up for Kenyan Airways while Charles Clayton, CEO of World Vision UK, made droll remarks about how sorry he was that he was the only one with a First Class ticket (the flight having been full by the time he booked). In the end he gave his seat to John Schenk, who had hurt his back.

The flight was 'free seating' and I found myself at the emergency exit door, thankful to God for an extra six inches of leg room. Sitting between me and the window was an Arabic-looking woman and her two children. She had what looked like tattooed feet, but it was explained to me later that this was some kind of henna-based paint that gradually wore off.

On her lap was a baby wearing only a T-shirt. It looked to me as if she just let the kid relieve himself on her own clothes, but I tried not to notice. Maybe she had a towel secreted in the voluminous folds of her many garments.

Every now and then she produced a large breast and stuck it into the mouth of the baby. The first time she did this I actually thought she had produced some kind of leather bottle from her pocket, so easily did she pull it out that it seemed not to be attached to her. Oh, hello! Errr, excuse me for looking, I thought that you were feeding the child a dead cucumber.

Feeling embarrassed for no good reason, I concentrated harder on reading my paperback. The boy next to me was about ten years old. He managed to crush five or six biscuits into crumbly powder and litter the seat and floor.

With these interesting companions we flew first to Lusaka in Zambia, then to Nairobi. We got in just before midnight and had to wait while the customs people 'ummed' and 'oohed' about our video equipment. They also X-rayed our suitcases and wanted to ask questions about mine, which had my portable printer in it. When I said it was a computer printer they said it would have to go into bond. This was plainly ridiculous since they were permitting me and four other people to take much more valuable laptop computers into the country. Just an exercise in petty authority. Our Kenyan colleagues, accustomed to this nonsense, argued their way through.

Dehydration Can Kill. But Not If You're British

Off to Somalia next day, but not without drama.

Charles presented himself for the car saying that he had had a rough night with very severe diarrhoea. Everyone had lots of advice for him.

'Take this for your nausea.'

'Take this for the runs.'

'Drink lots of mineral water.'

'Eat some dry bread.'

'A whack on the side of the head is good for that. It'll distract you.'

At the airport he staggered around. Soon he was having a fainting turn which quickly faded. He sat on the ground by a wall and I sat beside him. He was hardly up to talking, although he was making an effort to stay in touch. Finally it became clear to him what seemed pretty clear to the rest of us. He could not endure a three-hour plane ride to Baidoa.

He agreed to go back to the hotel with Leo Ballard, Africa Relief director, who had turned up to send some supplies with us. As they started to walk off towards Leo's car, Charles stopped by Aba Mpesha, our local director, to say good bye. The next thing I saw was Charles sliding down and Aba having a job holding him.

I leapt up and managed to get my arm under Charles' head and shoulder and lower him gently to the ground. People crowded round. Someone produced what looked like a pillow slip and made a useful breeze with it.

A young man with a close-clipped beard knelt down and took Charles' pulse and started yabbering away in Italian. He seemed to know what he was doing and I guessed he was a nurse or a doctor. He was asking questions.

'Margaret', I called out, remembering that she had told me she spoke a little Italian. She tried to translate what the fellow was saying.

Meanwhile, as the nausea built, Charles was breathing fast as if he was having a fit. Eventually he started to calm down and recover. He opened his eyes and began to come round. In five minutes or so he could stand with help, and by then the ambulance had come. We helped him in and Leo followed in his car. By the time the ambulance pulled up at the first aid station Charles was OK. Leo took him back to the hotel.

Charles was so weakened by the walk up to his room that he fell on his bed fully clothed and slept for five hours.

I concluded he was dehydrated. The same thing had happened to me in the past. It was an experience in Lebanon that brought home to me the value of the Oral Rehydration Therapy that prevented one becoming weakened through dehydration.

Charles' case showed the dangers of this condition. It was easy to see how it could kill children or adults already weakened by malnutrition. Charles recovered in the end because he was healthy. Kids in Hut 1 could not. They died within hours of a major diarrhoea attack.

Sea Sick To Somalia

Meanwhile, Dan the cameraman and I had gone up in the smaller of two twin-engine planes. It was a Piper Aztec with engines that did not seem to work together. As a result the plane described a gentle corkscrew all the way to Baidoa. Dan and I were almost green when we landed and very much in need of a walk and some deep breathing. Three hours and forty-five minutes of pukey flying.

World Vision's Bernard Vicary, from Melbourne, was waiting on the air strip as we approached. We circled for twenty minutes while they got a Hercules off the strip. As we came down, we saw the huge US army encampment nearby. The end of the strip was chewed up where the big transport planes had broken through the hot asphalt.

Our team was well served by some equipment that World Vision Australia provided. Everyone had a two-way radio, and satellite phones connected us to the rest of the world, even if at US$10 a minute. Bernard called up a vehicle and it soon arrived.

We had been delayed by the visit of ten American congressmen. The US army had over-reacted in a big way. They closed the airport for the whole visit (that's why we were circling) and shut down the entire town. Even aid agency people were prevented from visiting their feeding programs. This was hardly impressive, but it turned out to be one of the few blemishes on how the Yanks were handling their role. For the most part they were very effective. Not aggressive. Polite but firm.

Bridge Over Troubled Water

Soon we were at 'The Bridge' feeding centre, which was beside a bridge over a stream in the centre of town. Dan was shooting and we were getting the guided tour. Bernard was having fun with the kids and showing me round. The story was the same as in Mozambique. Malnutrition in evidence, but now controlled. There was danger from measles and other infectious diseases.

Around 4.30 we finished videoing. Bruce Menser, the man in charge of World Vision's team in Baidoa, asked if we would like to walk back to the base, something one could not do before the marines came. We all agreed.

Street Dangers

As we walked through the crowded and noisy streets, a small girl was knocked over by a Medecins sans Frontieres vehicle. Fortunately she seemed to only suffer gravel rash and a fright. A European woman in the car got out and looked her over, while Dan got the video camera on his shoulder and buried himself in the crowd too.

We were just recovering our equilibrium from this when there was a loud gunshot nearby. I froze, checking for bullet holes. Everyone around us went quiet. Bernard commented later that it was now so rare to hear a gun shot that everyone was surprised. From around a car came a man wearing an AK-47 and a sheepish look. We suspected he had let it go off accidentally.

Home Is Where World Vision Is

The World Vision base was an ex-hotel, rather like an improved version of the Commando Hotel where we had stayed on the Steve Vizard Ethiopia shoot two years before. It had been self-importantly named the International Hotel and was built around a small courtyard.

The World Vision base was an ex-hotel, rather like an improved version of the Commando Hotel where we had stayed on the Steve Vizard Ethiopia shoot two years before. It had been self-importantly named the International Hotel and was built around a small courtyard.

The rooms had no facilities save the beds and furniture we had brought in. Along the street frontage the rooms had been turned into offices; the living quarters were to the side and rear. On one side were three rooms with a proper flush toilet, a cold shower and a sink with two taps (cold and cold). The water was nicely refreshing at 5.00 in the evening when the edge was off the heat of the day.

Two tables were brought out into the courtyard and we ate alfresco under the stars. We were unsettled by a huge helicopter going over. It sounded like it was right on top of us but it was invisible. These machines were painted matt black so nothing reflected off them. You looked up to where the noise was coming from and saw nothing. The only way you could tell where they were was if they blocked out the stars. Spooky.

Next morning we had breakfast and I agreed to leave my Vegemite for Bernard. Susan was still there from the team I'd met in Mogadishu some months earlier, and Todd Stoltzfus was due to arrive back from R&R on the plane we would be leaving on. Mohamed Abdi, the Somali in charge of local staff was also there. He reminded me that he had studied agriculture in Gatton, Queensland, and pressed me (and everyone else) for a chance to come to my country. Apart from that there was Aidu, an agriculturalist from Mozambique; Mario, an agriculturalist from India; Cindy and Paul, two nurses from Canada; Bjorn, a Swede who was born in Africa and was acting as base organiser; and Bruce, in charge from the Sudan program.

In addition World Vision had about twenty local Somali employees whom we met the next day for afternoon tea. All the men had Mohamed in their names somewhere.

On The Road Again. The Back Of A Truck

When we went out we took two vehicles. World Vision had not purchased any ourselves because of the risk of theft; instead we hired local vehicles and drivers. This also added to the local economy. This day we had two Toyota utilities. The back of the second one had seats along the side, and I sat up there, in the open air, with Jacob Akol and Dan.

We went down the road towards Bur Hakaba to visit the Rowlo feeding centre situated behind CARE's headquarters. Here we were greeted with great joy by the local people because we were picking up their sheik to take him back to visit his now deserted village, also called Rowlo. Everyone wanted to come with us, but the sheik and his two brothers and two sisters (or it might have been one wife and one sister, or two wives) climbed into the back of our ute.

The sheik was over the moon. He shook everyone's hand vigorously. He was going home.

Before we left Baidoa the marines stopped us at a checkpoint. They asked if we had any weapons. The other car was carrying an automatic rifle which they disarmed and took away to check if it was registered. It was, and they returned it and sent us on our way.

We saw road works being accomplished by the huge bulldozers that had been flown in. They were massive machines. Everything about this army was big. Even the jeeps looked like scaled down trucks. I'd never seen a Hummer before.

At first the shoulders of the road, which was fast and smooth bitumen, had been cleared back about twenty metres, but soon we were into uncleared territory. Tall thorn bushes grew close to the road, making forward vision more difficult and providing good hiding places for ambushers. It was obvious why road clearing was a priority.

The Sheik Of Rowlo

Finally we came to Rowlo. The sheik took Graeme Irvine by the hand and enthusiastically showed him around.

The community had left to walk to Baidoa ten months before. The sheik said they were a faithful Muslim community and believed in peace. There were no weapons in the village. Other less religious communities had begun to act as bandits and had looted their sorghum stores. Eventually the banditry and the poor harvests led to the decision to head for Baidoa. Remarkably, the sheik managed to keep them together.

'Out of a total community of 3,000 people', reported the sheik, '400 died in the fighting with the other communities. One thousand three hundred died of hunger. Only about 1,000 of us remain.

Bernard reported that fifty-seven per cent of the people from Rowlo died within the first two weeks of their arrival in Baidoa. But by then World Vision's feeding program had begun to have the desired effect.

A Miniature Uluru

It was time to eat dust again. We rejoined the bitumen and drove down to a miniature Uluru. This was Bur Hakaba.

Before arriving at the rock we stopped briefly at Dacar (pronounced Da-hah), where the local sheik showed us around the feeding centre. The familiar pattern of malnutrition but good recovery rates was repeated. Of course, it was not right to say the problem was over merely because we were controlling most of the hunger-related deaths. Every feeding centre had its critical cases whom a decent cold or measles would kill.

It was hot again and the sheik served us sweet Arab-style tea. There were speeches which fortunately I slept through. Graeme said he almost fell asleep too, but he couldn't afford to because he was the one expected to respond. It was very relaxing travelling with the president.

At Bur Hakaba we had placed the feeding centre in a building originally erected to house British troops. It had the familiar rooms full of cases in descending order of desperation. I did a piece to camera showing that 'the money does get there'. Here, sixty kilometres from Baidoa, in one of the most difficult places World Vision had ever worked, the  Unimix was being made and put in the mouths of the suffering.

Unimix was being made and put in the mouths of the suffering.

Typical of our vision, the team was not content simply to feed those who came to the centre. Their goal was the restoration of the hungry, wherever they were. So Susan had organised a team of 'house visitors' who went house to house looking for bad cases and bringing them in. They were finding some every day.

I took a photo of a house visitor with her bag labelled World Vision House Visitor. Susan told me this woman had learned just that morning that her husband, missing for three months, had in fact been killed by the soldiers of Siad Barre. She had come to work and done her duty just the same.

I took a photo of a house visitor with her bag labelled World Vision House Visitor. Susan told me this woman had learned just that morning that her husband, missing for three months, had in fact been killed by the soldiers of Siad Barre. She had come to work and done her duty just the same.

Outside Bernard was teaching a group of young boys to say 'G'day' and 'Carn the Blues'. I asked if the kids were good singers and Bernard said, 'Let's get the girls to sing'. I was expecting children, but he actually meant the female staff. Five of them formed a choir around one show-stopping lead singer. Earlier I had pointed her out to Graeme for the way she danced between the Unimix bowl and her charges. Now she led the group in the singing of three songs.

The first was about World Vision, although it came out sounding rather like 'World Division'. The second was about Bernard, and the third about Susan. Diana Ross and the Supremes could not have done better!

We climbed back into the cars and sped off home. On the way something pinged off my cap and fell into my lap. It looked like a bee except it was about as big as my thumb! I yelped, whacked it onto the floor of the ute and stomped on it, much to everyone's amusement. Jacob assured me that they didn't bite, or if they did, you wouldn't notice because you'd be dead. I think he was joking.

British Pluck And Recovery

When we got back to base, Charles was there with a remarkable story about flying to Mombasa then persuading some US marines to fly him up to Baidoa in their Hercules airlift. He told me how grateful he was to me for simply being there. I assured him that if we stayed with World Vision long enough and did more trips like this, he would undoubtedly get the chance to reciprocate.

How Not To Do A Food Distribution

We held a communion service, led by Graeme, to begin the next day. Then Margaret, Bernard and I waited around the base while everyone else went off to Xarte Qanle (pronounced Heart de Carnlee) to see a World Vision food distribution.

Food distribution was a tricky business. It looked easy but it wasn't. World Vision had a lot of experience built up over many years, often by doing it wrong and seeing the results. Some other agencies were just learning their lessons in Somalia.

Russ Kerr, World Vision's vice president for Relief had earlier described one distribution he had witnessed. A truck simply pulled up to a walled compound and dumped bags off the back, leaving distribution to the locals and control to the French soldiers who were with them. Naturally there was a riot. People were crushed and trampled. The soldiers gave up in disgust. Russ felt that weaker people were probably killed, and certainly the ones most in need of food did not get it.

I had begun to call this the 'dump-and-run approach'.

A few agencies maintained they were only in the food delivery business, not the food distribution business. Distribution, they argued, was someone else's responsibility. But such a position was plainly irresponsible unless they knew there was a proper distribution system in place once they had delivered their part of the process.

And How To Do It Properly

The difference with a World Vision food distribution was the work we did in advance. We spoke to the local chiefs and set up a committee to take responsibility for the distribution. They listed the people who were to receive food and a system for recording receipt. When the trucks came, people were organised into orderly lines and the distribution went quickly, efficiently and safely. The whole process was monitored, so that we could guarantee the food got to the right people.

If things got out of hand, we stopped distributing food immediately, put everything back on the trucks and went away. Negotiations would begin again to correct the problems and distribution would recommence.

A few weeks after our visit things did get out of hand at a food distribution in Dacar. A television crew happened to be present and reported on what they called 'the food riot'.

What they were actually seeing was World Vision's operation working properly. Some people tried to break out of the queues. Hungry people can be desperate, even if they know there is enough food for all. When this happened, and while the soldiers were trying to control the crowd, the distribution was stopped, the trucks reloaded and the supplies taken away for another day. At most, a bag or two of food was 'lost'.

Distribution began again the next day, without the benefit of television.

It found it impossible to understand how any person or agency with a genuine concern for the people of Somalia would not want to ensure that there was something enduring left after the food had been dumped. Whether we played a part in that longer term strategy or not, I knew we had to operate in a way that supported such a strategy. This meant, for example, extending distribution into rural areas to prevent people from coming into the epidemic-ridden towns.

This particular morning the army was to provide an escort for our group, and it turned out that the advance guard of Australian soldiers, thirty-five of them, was part of the escort. I kicked myself that I didn't go. Nevertheless, after a quick phone call, Margaret, Bernard and I arranged to meet Major Dick Stanhope, the advance man for the Aussies. He was supportive and talked about the better ways the Australians were going to treat the aid agencies.

The subsequent visit by the Australian soldiers was a high point in international involvement in Somalia. From all reports they did us proud.

Watching The Passing Parade

We returned to base and I waited outside our front gate for the others to get back, watching the passing parade of Baidoa. A tall man in a ragged coat, a single article of clothing like a shirt hanging to his ankles, wandered about aimlessly hand in hand with a small child.

Large carcasses hung in the open, dusty air in a kiosk-style shop across the road.

A woman used her sandal to chase away a group of men for making cheeky remarks. She was selling sweets from a metal tray in her lap which she banged with a spoon to attract attention.

Half the vehicles that passed by were wearing agency stickers and flags: CARE, GOAL, Concern, MSF, Red Cross and World Vision.

Yet Another Feeding Centre

Our colleagues eventually returned and we set off to see the feeding at the Rowlo feeding centre. Again the sheik met us.

The contrast between the potentially pleasant village scene where we had taken him the day before and this hell-hole could not have been more stark. Not that the Rowlo feeding centre was any worse than the rest. It was simply the same. Too many people crowded together into too little space. Too many in the feeding centre in bad condition. Too many skeletal kids walking around slowly and heavily. Too many sitting on the ground, eyes dropping and heads lolling. Too many coughs. Too many with measles.

Here it goes again, I thought, suddenly weary. There would be deaths there that week. At least no-one would die of starvation. Something else would kill them.

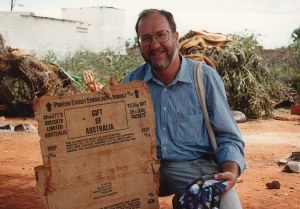

I went out and sat under a tree. A carton lay on the ground. It had been flattened out to form a piece of roofing for a hut but had slid off. The carton had printing on it: 'Gift of Australia. Protein Energy Emergency Product. Arnott's Australia'. High Energy Biscuits. The aid did get through.

I went out and sat under a tree. A carton lay on the ground. It had been flattened out to form a piece of roofing for a hut but had slid off. The carton had printing on it: 'Gift of Australia. Protein Energy Emergency Product. Arnott's Australia'. High Energy Biscuits. The aid did get through.

Russ Kerr was sitting there too and saw my melancholy look. 'You can visit too many of these feeding centres', he said.

I knew what he meant.