SOMALIA 1992

Over the years, programs like Sixty Minutes and A Current Affair have been useful allies in telling the stories that matter to World Vision. It could never be said that these programs ever ran a 'World Vision' story. They always retained a firm grip on editorial control, and were always determined to tell the story their way, whether or not it suited World Vision. I have never objected to this, nor wanted it any other way, even though in a business as complex and risky as ours there have inevitably been some bad stories to complement the good ones.

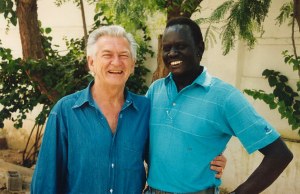

In this visit to Somalia, this alliance had an important extra dimension because the reporter for Sixty Minutes was the former Australian Prime Minister, Bob Hawke. Now, for the first time, I was able to walk alongside people who were, or who saw themselves, as the leaders of nations. I was not surprised to discover them all to be both extraordinary and ordinary. They were humans with faults, yet they carried around them larger-than-life myths and charisma. Such power could be used for good or ill. A ready smile, and a winning manner, were no guarantee of sincerity or authenticity.

5 Star Hotel At Last

I had to admit I was lucky. I was staying at the Norfolk Hotel, Nairobi with the Sixty Minutes crew. It was the nicest hotel I'd been to in Nairobi. Far better than the musty place I'd stayed in the time before, the name of which was now extinguished from my memory. Unlike the other rooms in my block, mine had a balcony with large airy French windows and a view over the pool. The weather was overcast, occasionally drizzling rain and quite cool.

I connected with Jacob Akol after someone from World Vision s Kenya office called home in Melbourne to see where I was. Jacob admitted that the fax with my flight details was probably under a pile of papers on his desk. He was busy, poor fellow. I hoped his state of ragged-edge harassment didn't show in the briefing he was planning for me and the crew at 12.30 p.m.

Just after noon, I called Andrew, the Sixty Minutes director/writer/producer, and arranged for the briefing to be at five. Jacob was relieved. The problem was Bob, who was off with someone from the High Commission. Shopping. Then he was out for a game of golf.

Andrew said, 'You know Bob. He's got to get his game of golf in.' Yes, I had heard that. At least the man had priorities that were likely to lead to a long life.

The Man Who Told The World

Besides Jacob and myself, there were four people in our crew: Andrew Haughton (producer/director), Paul Boocock (cameraman), Ben Crane (sound) and Bob Hawke (reporter). The briefing went very well and the relationship among the six of us began to take good shape. It was quickly clear that Andrew had an appropriately high opinion of Jacob, describing him to Bob in the words our office had given him: 'The man who told the world about the Ethiopian famine'. This was true; it was Jacob who had persuaded Michael Beurk of the BBC to go (without Ethiopian government permission) to the famine valleys. The government had been trying to pretend they didn't have a problem.

Meeting Bob Hawke

I soon discovered that Bob Hawke swore quite a lot and I began to wonder how this was going to go. To his credit, he soon got onto the World Vision wavelength, especially by the time he was living in the Mogadishu compound with a dozen World Vision people. His expletives became less frequent but more effective.

During the briefing Jacob mentioned that Ali Mahdi (who was claiming to be President of Somalia) had been deputy to General Aideed (who was claiming to be in control of most of Somalia). Bob commented, 'That's the trouble with bloody deputies. They're never satisfied.'

Cheap Drinks, Guns and Drugs

Around 6.30 p.m. Bob was due to leave for the Australian High Commission for the fortnightly 'free bar'. He insisted we all come along. We were soon engulfed by a hundred or so people of various colours, creeds and states of inebriation.

Lacking Bob's social skills, I spent most of the time chatting with the Deputy High Commissioner, Peter Hooton, whom I had met before and who knew World Vision well. He told me that you could buy a Kalashnikov automatic rifle in the Eastleigh market in Nairobi for about US$20. He suspected they came from Somalia. He also revealed that each day, five plane loads of khat flew out of Wilson airport for Somalia. This was the drug the people chew. It made them crazy.

Such trade was just obscene. To a country starving for food, there were still unscrupulous people who would supply drugs for a profit. They showed no concern for the impact on a country in which one drug-crazed person with a rifle could quickly become a mad murderer. The pilot who later flew us into Mogadishu said the daily number of flights was more likely to be ten.

Somali Hitchhiker

We were up at three for a four o'clock departure to the airport. Our plane was a Cessna twin-engine ten seater, so there was plenty of room. The pilot was Peter, an Aussie originally from Hamilton in Victoria.

Hitching a ride with us was a professor from Canada. A large Somali man, Professor Siad Togane taught English Literature at Concordia College in Montreal. He was coming to Somalia to represent the Somalia Peace and Consultation Committee, a group of expatriate North American and European Somali intellectuals. The steering committee carefully had five members, each representing a clan faction, 'since Somalis are obsessed with clans'.

Togane had previously been in Mogadishu in June 1991 but had left after eight days because he was afraid that someone might kill him by accident. They had even shot at his plane as he was coming in to land. We anticipated no such trouble this time.

Divided Mogadishu

It took just over three hours to fly up to Mogadishu. The city was divided. Part was controlled by Ali Mahdi who called himself President, having been elected by some clans in an interim capacity. This was what triggered the war for Mogadishu, because General Aideed refused to accept their declaration. He shelled the city, already almost destroyed in the war to get rid of the previous dictator, Siad Barre. It resembled Beirut, although since there were fewer high-rise buildings the damage was not as dramatic.

Our first appointment was with Ali Mahdi in the small area in the city's north that he controlled under a cease-fire agreement. Thus we overflew the main Mogadishu airport and put down on a deserted sandy airstrip north of the city.

It was due to be a busy day for the leaders. James Grant, head of UNICEF, was in town. The next day, the first of the UN peace-keeping soldiers were due to arrive. Many thought this would trigger violence, since Aideed had objected to an expansion of UN military presence. Also, John Schenk, a member of Jacob's communications team, told us soon after he met us at the plane that two bodyguards of the Ministry of State had argued and shot one another!

All this had made it difficult for John to get vehicles for us. But he had good cooperation from Alistair Duncan, the head of the UN in the north of Mogadishu. Two UN vehicles came, accompanied by two utility vehicles with large machine guns mounted on the back and festooned with young men carrying machine guns. These were called 'technical vehicles' and the people on them were therefore called 'technicals'.

Women Organisers

We charged off at a dangerous rate over the sand-dunes and past an old battle ground with the rusting hulks of shattered tanks and personnel carriers littering the landscape. Fatuma, the young woman who was organising everything, said it was a place Siad Barre had fought and lost.

John said the women do all the business here. 'If you need something done, you find that the women make it happen.'

I asked Fatuma how long there had been peace in North Mogadishu.

'Six months', she said. And indeed, it did seem peaceful. There were few people carrying weapons, and those who were appeared to be soldiers acting in a policing role. There was a traffic policeman at a roundabout who saluted sincerely as we skidded around him.

As we drove through the busy but orderly streets we noted the occasional business springing back to life. There were many one-table shops, and one or two restaurants or bars. Jacob said, 'This place needs life, not death. It's important for life to come back. It needs parties, music.'

Meeting A Presidential Contender

Our convoy, with enough weaponry to guard the coast of Queensland, drove directly to meet with Ali Mahdi himself. He was a pleasant man with a friendly manner who appeared to have accomplished the international public relations task better than his opponents.

His problem was that he controlled an area about the size of Fitzroy, Melbourne. It might be peaceful, it might be starting to return to relatively normal life, but it wasn't Somalia.

The crew filmed a long interview with him, and I got the impression that Bob thought him rather shallow. There was not a lot behind the smile and the easy manner. Just the same, most of us were buying the 'we're the good guys, Aideed's people are the bad guys' line. Later encounters taught us things were not that simple.

We were treated to lunch. A spaghetti and meat sauce entree followed by a very tasty fish main course. Rather too much, really, and totally out of proportion with the situation. Just the same, hospitality is something to be received in the generous spirit with which it is given; after all, God's generosity is itself rather more extravagant than any meal anyone ever offered.

Alistair Dawson, UN rep, joined us for lunch. A white Kenyan and the former manager of five-star game park hotels in Kenya, he now owned a successful restaurant and bar in Portugal. John said he was really getting things done. He was also putting his hotel experience to work by ensuring that UN staff ate lobster and fresh fruit at less than the cost of regular rations. Some miracle of knowing where to go and whom to encourage.

Refugee Tour

After lunch we visited what might have once been the Saudi Arabian embassy. Now it was a dilapidated three-storey shell with an empty swimming pool and a bitumen tennis court. Hundreds of people lived there in temporary refuge. Their general health seemed reasonable despite the crowded and basic living conditions.

Ali Mahdi's elegant lawyer wife, Nurte, guided us. Bob came across some who were in much worse condition. 'That two year old won't last another day', he suggested. 'You'd be surprised', I counselled, 'how fast kids bounce back if they get proper intensive feeding'. It was not clear, however, that they would be getting what they needed.

Next we went to a Red Cross Refugee Centre on the outskirts of town. An old naval academy stood on a large allotment near the sea. It was a bare, four-storey building with tiled floors and scarcely a splinter of woodwork left inside. The banisters were gone from the stairs. The window frames were gone. Only the wooden doors remained on some rooms.

The reason? The shortage of firewood for cooking.

The building was a landmark in the area, so it was also a target. It was spattered with shrapnel damage and several large shell holes. Families lived in the rooms and corridors with their goats and cooking fires.

But inside was better than outside, where thousands crammed into stick and cloth hovels with hardly room to walk between them. Another epidemic time bomb waiting to ignite. Please, God, allow no child to get measles here.

John Schenk remained in constant contact with the UN office via one of their walkie-talkies. They called us up by our initials, 'WV', except it sounded rather odd to hear World Vision called 'Whisky Victor'.

Crossing The Mid-City Border

All morning there had been debate about how we should go from the north to the south side of town, where World Vision had pretty much taken over the World Concern compound for the weekend. The south was controlled by Aideed's United Somali Congress (USC). A more direct route by the coast was preferred, but finally word came through that it was not safe. Too much shooting. So we went the long way round.

As we moved along a wide street, our technical vehicle stopped and waved us on at a road block. This was the end of the Ali Mahdi zone. Nothing distinguished the strategic change in leadership; it was just another street scape. But our technicals dared not continue. Two hundred metres away was a second road block beyond no-man's land. Another technical vehicle awaited to take over our protection.

Actually, the protection was more for the vehicles we were travelling in than for us. No-one had so far taken pot shots at foreign workers or journalists. We were welcome here. But cars were precious and valued. An unprotected car was easy to steal if you had superior weapons.

Fire Fights At Our Base

We did not go immediately to the World Concern compound but stopped for a moment at UNICEF. Here Leo Ballard, the manager of our relief program for East Africa, joined us with some interesting news. At breakfast time there had been a fire fight right outside the compound gates. It was a demarcation dispute. One clan was providing protection for the compounds. One of their technical vehicles sat in the yard and a dozen of their well-armed men were at the gates. But another group wanted the work. There was a brief skirmish and the newcomers vowed to return 'tonight' to do 'our' boys over.

Leo thought it was all bravado and that there would not be any return visit (his judgment proved to be correct). On his advice we went on to the compound.

World Vision People Come From Everywhere

Two identical houses stood side-by-side. World Concern occupied one; Swedish Church Relief the other. Each had a pair of open-air rotundas by the front verandah. Leo spent most of the next two days sitting in one of these negotiating deals, setting up the World Vision program in Baidoa.

We met the World Vision people. Leland Brenneman from Mozambique would be the project manager for the next month or so; he was from Virginia and proud of it. With a dry wit, natural charm and apparently unending patience, he had good things to say about the Australians working in Mozambique.

Todd Stoltzfuz came from the Sudan program. He was also American, but younger and quieter, almost shy. He smiled a lot and served everyone quietly and well.

Susan Bander was a woman in her late thirties, a nurse from Alaska, although originally from California. She was certain she had met me before, and eventually realised it was a few weeks earlier in the foyer of the Holiday Inn, Monrovia, California, where she was doing orientation at our international office.

Susan's boss was Dr Hector Jalipa, who served with great distinction in Mozambique before going (with World Vision Australia sponsorship) to Harvard to complete his Master's in public health. He returned even more committed to World Vision and would undoubtedly make a good impact. A quality man with a big heart.

Africa Correspondent

James Schofield (ABC Africa Correspondent) was also there. He wanted an interview with Hawke, but Andrew wouldn't have a bar of it. 'I don't trust reporters', he said to me behind his hand, without any awareness of the irony. He seemed worried about Sixty Minutes getting scooped.

James was not put out by being refused and we chatted. He had objective comments on the aid effort so far. 'CARE are doing a good job, if a bit thrown together', he said. 'Nearly all of CARE's first shipment into Baidoa was looted.' I didn't recall this being reported. 'The Red Cross have great coverage, but many 'kitchens are not supervised.'

John said he'd asked Red Cross what they supplied and was told, 'Rice, beans and oil'. But when he visited a Red Cross feeding centre, the kitchen staff said they only had rice. He presumed the rest had been sold. This was a common pattern, not just a Red Cross problem. Anyone delivering food faced the same difficulty. There were few reliable local partners.

James asked me what I thought of Ali Mahdi. I said I was impressed with the peaceful life in his area compared with the visible display of weaponry down here in the south. Every man was carrying a gun here. Schofield replied by suggesting that Aideed was the only person with 'the capability of governing Somalia'. 'Ali Mahdi is only a banker', he said.

'Seems a better qualification for President than soldiering', I commented. 'Not too many soldiers who became presidents in Africa turned out to be any good.'

'I suppose you're right', conceded James generously.

The Constant Sound Of Battle

Two or three times an hour we jumped as an automatic rifle let off a few rounds. Clearly most of this was either frightening carelessness or boredom. Pity the local cat population. Soon we stopped jumping when we realised no rounds were sailing over our heads.

We heard the crump-crump of shells landing somewhere distant but it stopped as soon as it started. During the night there was a fire fight that seemed to go on for three minutes or so. We were told in the morning that it was simply people manning the road block at the end of our street. They had fired warning shots over a vehicle which took a wrong turn.

'The real worry was being hit by accident. The week before, a guard in the Swedish Church Relief compound picked up his rifle by the barrel and it went off. The bullet went through his top lip and exited in a bloody mess out the back of his head. He died instantly, a victim of his own carelessness.

Leland Brenneman suggested someone should invent a gun virus 'You know, there are these computer viruses', he explained. 'They get into your computer and ruin it. Well, someone should invent a round that can be smuggled into ammunition. When it goes up the barrel, it renders the weapon useless.' I thought it was a very good idea. Perhaps we should get Australian Defence Industries working on it.

One of our guards was just fifteen years old. Jacob asked him, 'Why are you not in school?' He replied, 'There are no schools. I can only learn to use a gun.'

Imposing Ourselves

The generators ran in the compound from 6.00 to 9.30 p.m. After that it was lights out. This seemed an early time to retire but I was ready by eight. The early start and remaining jetlag conspired to get me down while the lights were still on. I bunked down on a stretcher (they called it a 'camp bed') while Leo slept on a double bed in the same room.

Obviously we could not continue to impose on World Concern for accommodation. They did not appreciate the amount of traffic World Vision was generating, although to their credit, they tried to conceal it. Our involvement with World Concern and Swedish Church Relief was not without problems for these partners. Our methodologies were quite different. They planned to take things slowly, remain small. This was commendable, but Somalia at that moment also needed the more dramatic World Vision approach. An approach that helped to put the issues on the world's agenda and generated more response. Nevertheless, the USC asked questions about the relationship when they saw us coming with film crews and journalists. It was an additional strain that World Concern could do without.

The Illusion That We Have The Answer

The next morning we made a courtesy call on the headquarters of the USC. A man came over and asked me, 'How many UN troops do you think it will take? 10,000? 20,000?' He was an ex-pilot with long defunct Somali Airlines. We said we did not know, but his question was rhetorical. No number would be sufficient in his view.

''No-one can impose their will on me. People come to Somalia with their solutions. The solutions must be found right here in Somalia. I am the problem', he said, holding himself up as a metaphor for Somalia. 'I am the solution. The BBC asks people who have been here two days what is the answer. They don't ask me. They should ask me. The solution is to get Somalis to dialogue. The UN can assist, but not by imposing answers on me. No-one can enter my house and take my gun away.'

Where You Stand Depends On Where You Sit

Bob asked the Secretary-General whether the USC were interested in talk and negotiation with Ali Mahdi.

'He will have to come as just another party leader. He cannot claim to be President', replied the Secretary-General. 'I was one of twenty-seven people who mediated between Aideed and Ali Mahdi. In May, they said, “Aideed is Ali Mahdi and Ali Mahdi is Aideed”. They signed an agreement. Next morning Ali Mahdi renounced all the agreements and attacked Aideed's headquarters.'

Jacob said in my ear that this was just not true. Ali Mahdi had nothing with which to attack anyone.

'We heard that Ali Mahdi was importing money for his war against us so we fired over the airport to prevent the plane carrying this money from landing'. the Secretary-General explained.

Jacob asked about the 'election in Djibouti' where Ali Mahdi was proclaimed interim President.

'This was not an election', said the Secretary-General. He claimed the Italians were behind it. When in doubt, blame an outsider. Xenophobia is a favourite weapon of the powerful coward.

'When Siad Barre's forces returned within seventy kilometres of Mogadishu, Ali Mahdi did not attempt to join the fight. He wanted Siad Barre to come. Even though he was supposed to be a member of the USC, he did nothing to help.'

What Is The 60 Minutes Angle?

I asked Andrew whether he was planning to deal with the issue of the UN's responsiveness. Had the world been slow to respond? Why? What should have been done? What was required now?

Andrew described this line as 'worthy but dull'. His approach was to show the need, to say that despite all the difficulties the humanitarian aid effort was important and worthwhile.

Bob wanted to add another dimension and Andrew went along with this gladly. Both Ali Mahdi and the USC Secretary-General had shown a desire for dialogue. There appeared to be some common ground. If we could get Aideed to say he would talk, Bob said he would take this message back to Gareth Evans. We could probably bring international pressure to bear to hold them to their word, especially if we had both statements on film. Ali Mahdi's was a in the can.

Going Where The Pictures Are

Andrew was keen to see the gun market. No-one was keen to take him there. It was dangerous 'because of test firings'.

He also wanted to film in the port, which had been closed for two weeks. Everyone was leery about taking a camera crew there. 'It's the worst place'. said John, but agreed to ask the Secretary-General.

He said, 'No problem. We can help you do that.'

We presumed this meant sending his own militia for protection, but as we left he said to John, 'The best way you can do this is to discuss it with CARE'. CARE was responsible for port administration. This statement proved that the USC had no real control over the port. We soon discovered that neither did CARE.

Getting Organised

Around 10.30 a.m. we were back at the World Concern compound, and I was sitting in one of the rotundas eavesdropping on Leo's negotiations with a thin, middle-aged lady dressed in flowing bright red robes. She was Anna, who owned the compound houses and was organising everything else World Vision needed locally. Suddenly there was the sound of shells exploding some distance away.

Anna said, 'It is just protest about the UN troops.'

'But they are not coming today', corrected the young man who was helping her.

'I know', she replied, 'they'll protest anyway.'

Then she turned to Leo with some advice. 'Don't trust my people, Leo. Don't give them a chance to loot or kill. If anyone goes into your home without invitation, fire them on the spot.'

Chatting With A Former PM

Time dragged slowly as John tried to find out whether we could film in the port or the gun market. I sat on a swing seat with Bob and our conversation covered a wide range.

On John Kerin (then Minister for Trade and Development): 'He's an honest, decent guy. Despicably treated by Keating. Kerin has an odd sense of humour. He tells the worst jokes. So bad you don't even laugh.'

On Gareth Evans: 'Best Australian Foreign Minister ever. A great mind. Quick. You never need to explain things to Evans. He catches onto ideas immediately.'

On Graham Kennedy: 'He has a social conscience, you know. I've been to his house and when it's just him and Bob he opens up. I think he's reluctant to show his social conscience because he thinks it's at odds with his public persona.'

On Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe: 'There's a harshness, a ruthlessness about him'.

On Museveni, President of Uganda: 'Far and away the best African leader I have met'. Jacob was surprised to hear this.

Doesn't Look Good At The Port

John was back from CARE. They had said the port may open tomorrow, but they said that every day. It was overrun by unconnected groups of bandits. 'CARE said they would take us down there, but they really don't think it will be possible to do anything', John said.

Andrew decided to go and try for some establishing shots and an interview with the CARE guy just saying all the above.

More Madness

But first we went to the hospital on the outskirts of Mogadishu, La Folle.

Wait a minute, I thought; didn't this mean 'madness' in French? Des herbesfolle, the mad herbs, are weeds. A coincidence? Or a deep irony?

Graeme Irvine had once interviewed the doctor here. She seemed a modern saint giving refugees shelter on the extensive property she owned. Now she was away, and no-one was quite sure where she was. No-one was alleging wrongdoing, but there was an odour in the air.

World Vision had put in 300 metres of cotton sheeting here because the previous sheets had all been torn into bandages.

We toured the hospital briefly and noted that there were few patients. The reason was that no-one felt they had the authority to admit patients without the doctor present. Susan Bander planned to correct this.

Bob was shocked to see the people's condition. It was much worse than in the north of town. We met one young boy, about ten years old, extremely bloated by fluid retention.

I asked questions about a young mother with a frail child. She was a 'widow at nineteen. The same age as my daughter! Her name was Filei Nur Ibraham. Her husband died in the fighting. Many days previously (she couldn't remember when) she had begun to walk into Mogadishu from her village sixty kilometres away. She had arrived the day before. Her child, a boy, Ahmed Mohamed, was eighteen months old. They had started feeding the child yesterday and were also feeding the mother so she could improve her milk.

Aid Plus Guns = Unwelcome Compromises

We returned to the compound and Bob interviewed Jacob. Paul tried to get gunmen into the shot but they were reluctant to cooperate. So he resorted to subterfuge, pretending not to be filming when he was, and pretending to be filming something else when he was filming them.

Bob asked Jacob, 'We are sitting here in a compound with World Vision people, and we are surrounded by guns. Why?'

Jacob replied, 'We don't like it. But it is the only way you can work in Somalia. Aid needs protection. The only alternative is not to come here at all. Then you help nobody.'

The Mad Man At The Port

After this, John and I remained while the Sixty Minutes team went off to the port with the CARE people and Jacob. Their authorisation papers from General Aideed's people got them through two checkpoints and into the port proper. They were just setting up the camera tripod when a young man appeared. He had a gun and was very angry.

They suspected he was high on the drug, khat. No Somali-language capability was required to understand what he wanted. He wanted the cameras off his port. And he wanted it now.

Bob was quite shaken by the experience. He talked it through when they returned, retelling the story as other World Vision people came around to find out what happened. 'Crazy', he said with a dramatic and disbelieving shake of the head, 'he was just crazy'. He repeated it over and over.

It was quite clear that whatever General Aideed controlled, no faction controlled the port.

Testing the WV Finance System

Meanwhile, Leo and Leland had been negotiating. Leo had spent over $10,000 in a day and he seemed a bit shell-shocked. 'Here's a test for WVI Finance', he said. 'We need $10,000 deposited in a Djibouti bank account. We need it next week or Leland will be in deep trouble.'

Leo The Cool

A gun went blatt just outside the wall. Leo looked casually at his watch and said laconically, 'Ah. The four-thirty gun.'

Bob Talks To Our Wheeler-Dealer

Bob was interested in talking with Anna, the wheeler-dealer. She had lived half her life abroad when, from her middle twenties, she worked for the Siad Barre government. She was self-taught in English and came from a huge family, most whom had moved overseas during the war. She had stayed to look after the houses. Her former husband was an ambassador and they moved from the Rome mission to New York, Canada, Senegal. In Canada she divorced and her present husband was a businessman, but now jobless.

'World Vision heard I was someone they could trust', she explained.

She organised the trucks that were carrying World Vision aid supplies. Each vehicle came with its own security and driver provided by the vehicle's owner. Trucks she rented from a local company.

Bob asked her about the future.

'You cannot foresee what will happen because it might start with two guys and a stone and blow up to the sky. If the problem were only Aideed and Ali Mahdi maybe a future could be foreseen.'

Had the world been slow to respond to Somalia's needs?

'Almost everybody has been slow.'

Do you think the UN peace keeping process will succeed?

'If they succeed, it will be the most beautiful thing for Somalia. I know my people. I served Siad Barre for twenty years. Somalis are by nature soft-hearted. Even those who killed, they will cry and regret it. I don't know who to blame, but people don't know how to talk.'

'Many young men say they are going to hell anyway. They have nothing to lose. They have no merit with God.'

'We Somalis are impatient. We want to come from the bottom to the top in one jump. We don't count the cost. Whether people are killed is not important. I get depressed. I don't sleep enough. I'm hyper-sensitive. I become hopeless. But the young people are fresh. They come from the bush. They are not educated, not rich. They had nothing even before there was a civil war in which to lose things. They now find in the towns that in half a day they can make millions with a gun. The rich and the older people want peace. These others do not want peace. They say "We are here to mess things up".'

Bob asked her about Somali Fruit, the only unscathed business he had seen in the country so far. He had heard that it was protected. Although it hadn't operated for fifteen months, it was untouched.

'No, it operated until six months ago', she said. 'They are just lucky. The shells have no guidance. They just pull the trigger. Where it goes, it goes.'

'Lucky?' Bob responded. 'But it's entirely undamaged.'

'Just lucky.'

'Was it a big company?'

'Very big. It functioned beautifully. The Somali grapefruit is the second best in the world. And our papaya is near the top.'

Bob thanked her for talking with him. When she left, he turned in disgust. 'There's the biggest load of bloody hypocrisy you ever heard.'

Late Night Prophecy

We were planning to fly to Bardera the following day. We were told we would see the worst of the famine there, and we had been promised an interview with General Aideed.

In the evening, before the generators expired, we played Liverpool Rummy. Then Bob and Andrew had a game of Honeymoon Bridge and we retired with the news that our lights were going out soon. My Bible fell open at Psalm 23. Verse four read, 'Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I fear no evil; for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me.' Were we going to walk into the 'dark valley', the valley of death, tomorrow?

In the morning I noticed this was the verse of the day on the wall calendar. More than coincidence.

Inventing New Taxes

We went to the airport. It was the only part of Mogadishu I recognised from my earlier visit a decade before. John had a long negotiating argument with well-dressed people who wanted to charge landing fees and journalists' tax.

Journalists' tax? At the USC they had assured us that there were no fees for using the airport. Here was another place the General did not have control.

John's ambit claim was that none of us were journalists. Everyone worked for World Vision. Bob showed them he was not a journalist by flashing his purple diplomatic passport. They wanted to inspect it, but he refused to let it go. Wise man. They wanted to inspect our passports to see what our occupations were. We pointed out the elementary information that passports do not normally reveal this. Certainly none of the passports we had did.

The negotiation was important. Agreeing too readily would establish the currency for all those who followed. Finally we agreed to a $100 landing fee, and $20 for three journalists, whoever they were.

John and I discussed movies all the way up to Bardera. It was therapy against the day that was to come and we admitted it.

In The War Lord's Town

Bardera loomed up and we circled it twice to allow Paul to get some shots. It did occur to me that this was a little foolhardy. A lot of people down there had guns, and some might not. appreciate being buzzed. I was just preparing to say this when the pilot straightened up for his approach.

Clearly some food distribution was going on in the centre of town. A vehicle with a CARE flag on it was waiting for us. General Aideed was expecting us and we went to his headquarters in a two-storey house. The countryside was bare and sandy. Thorn bushes abounded but they had no leaves. It was a desolate place.

Meeting The War Lord

Aideed kept us waiting for over half an hour, and Bob and Andrew became increasingly impatient. Jacob wondered whether the reason was that retired politicians in Africa have bad reputations, since few of them retire gracefully. But the reason proved to be the time taken to prepare a statement that the General wanted to read to camera.

This was not only dull television, it was also a history lesson for us. The crew shot a "strawberry". The filming you do when you're not really filming. After twenty-five minutes (a magazine lasts only ten), the General stopped and Andrew said 'Change magazines, gentlemen'. Paul took the magazine off, put the same one back on again and they shot Bob's questions and answers.

Aideed was a trim man in his sixties with an easy-going manner but an air of power about him. He told us that he had been Ambassador to India and had got to know the Aussie Ambassador well at the time. He resigned his ambassadorship to lead the struggle against Siad Barre. So much was undoubtedly true.

He told us that the world was very confused about the true nature of the Somali crisis. Too many outsiders wanted to impose their solutions. They were sincere but mistaken. The problem was not 'simply that there were clans vying for power.

As we filmed, a Hercules aeroplane droned in with the second food delivery of the day. Today they planned four deliveries. This was only the third day that food had come.

Hoping to dispel the confusion, Aideed sheeted responsibility home to Siad Barre, with justification. 'He introduced a communist police state with instruments of torture and death.' There was a lot more along this line.

Finally Bob asked his key question about reconciliation. 'What process will you engage in?' We got a litany detailing Mi Mahdi's mismanagement and culpability in response. Bob pressed and Aideed said, 'If Ali Mahdi officially renounces his claim to the Presidency [we already had him on film saying he would be so prepared] then we will consult our partners in the new coalition. We will be flexible.' It was not exactly total commitment.

A Canadian reporter was having a frustrating morning trying to get an interview with the General. He told me the Red Cross had two trucks stolen at Baidoa the previous day. Here in Bardera the USC tried to take ten per cent of the food aid as 'security charge', but to his credit Aideed quashed the plan. The reporter finally got his interview when Andrew wanted to shoot reverses with Bob alone. We offered him a lift back to Nairobi as he had been hoping to get out on the Hercs, now well gone.

Food Riots

The General wanted to show us Bardera and insisted on accompanying Hawke personally. If he had a low opinion of retired politicians, he had just revised it.

In the market square, food distribution was taking place. It was immensely crowded and chaotic. Shots were fired over the crowd for control. I was standing on top of a stone wall trying to get a view over the crowd but the rounds mercifully went a lot higher.

One group of officials gave up trying to distribute food in the open market area and started to carry bags into a stone room. A man showed me an exercise book with a list of names and numbers beside each name. People argued with the officials with profound anger and ferocity. It felt like a riot, but it got no worse.

Bob did a stand up. 'This is the tragedy of Somalia. The aid is making a difference, despite the enormous difficulties. It is getting through somehow. And we have seen people recovering. But more is needed. Peace is needed. Stability.'

Yet Another Hopeless Hospital

At the hospital, three wards contained men, women and children respectively. The floors had been swept clean, but little else commended this as a place to treat the sick and dying. There was no furniture. No medicines. They had some Unimix, a little food. No milk for babies.

A group of three small emaciated children lay in a quiet, listless clump on the floor. 'Where are their parents?' I asked.

'In the other wards. They are just as bad.'

These children needed to be fed intravenously. Food by mouth they were throwing up immediately. Doctor Mohamed Kulan from Mogadishu had been there for two months. He said he had the needles but he did not have the solutions for the drips.

'We can at least feed some of them and they recover. For the rest?' He shrugged his shoulders.

Before he came, forty to sixty were dying a day. Now it was down to ten to fifteen. I reckoned I had just seen tomorrow's group.

The doctor and I sat by a young mother with a baby at her breast. She was Yustor and her boy, Isaac, aged nine months, was the size of a newborn. They had nothing to feed him but fortunately the mother did. The doctor was feeding her to bring her strength up. Mother and child were very thin, but she had spirit and strength.

The Story Is In The Can

Andrew announced, 'Righto lads. I have my story.' We returned to the aeroplane. He did not need to go to Baidoa and so we went straight to Nairobi.

On landing Bob asked if he could donate his Sixty Minutes fee. Could it be used to supply medicines to the Bardera hospital? I said thanks. His generosity was considerable and appreciated. But I was not surprised. So many people who visited World Vision's work responded in similar ways.

We arrived back at Nairobi around 5.30 p.m. and I managed to get the same pleasant room at the Norfolk Hotel.

Jacob And Bob Play Golf

Jacob and Bob were playing golf the next morning. Bob dropped hints that they would not want any novice golfers slowing them down. Jacob had a fifteen handicap. Bob said his was twenty, although it must have been less. He said that golfers always lie about their handicaps.

Jacob and Bob were playing golf the next morning. Bob dropped hints that they would not want any novice golfers slowing them down. Jacob had a fifteen handicap. Bob said his was twenty, although it must have been less. He said that golfers always lie about their handicaps.

I heard that Bob 'played terribly' on the front nine, but improved a lot on the back nine. Jacob won the front nine. They squared the back nine.

I never did work out whether Bob's back-nine turnaround was the result of Jacob having an attack of public relations common sense, or whether Bob really did get it together.