1992

There are few better places in the world to explore the relationship between Occupier and the Occupied than the Middle East. In Israel one encounters a vigorous debate around justice that is much more open and free than in many countries. One can quickly see the implications of stereotyping and myth-making as tools for creating and maintaining race hatred. And, as I had discovered in my earlier visit, one can come under personal attack without too much provocation on one's own part.

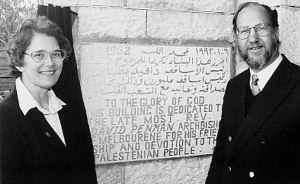

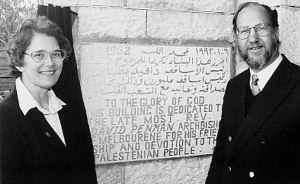

My next visit to Israel and the Occupied Territories was prompted by the desire of the Archbishop of Canterbury to officially open a West Bank community centre that World Vision Australia had funded and which was to be dedicated to the memory of the late Archbishop of Melbourne, David Penman.

Again there were plenty of incidents on which to reflect. World Vision's own response to development now clearly recognised that the roots of poverty often lie in oppressive structures. Our president reinforced the need for World Vision to respond by standing with oppressed people.

The experiences culminated in an extraordinary visit with a Serbian-Australian sponsor to see her sponsored child. As we spent the day together we heard her own story about oppression at the hands of Croatians that, for me, resonated with the Israeli/Palestinian experience. Yet I was amazed to discover that, while it was possible for her to see the prejudice of oppression in someone else's story, it was harder to see it in her own.

Dreams Differ From Reality

On the flight north from Australia I read From Beirut to Jerusalem, a big thick book written by Thomas Friedman, an American Jew who was New York Times correspondent in Beirut and Jerusalem in the 1980s. The writer was both a political journalist and a jew who had bought the whole Israel myth as a young man, but then had to face the reality of the way the Israel dream was creating injustice for the Palestinians. His viewpoint was uncommonly relevant.

At Zurich the connection to Tel Aviv was on Swissair, so I was spared the kind of interrogation I'd experienced when travelling with El Al two years before. Nevertheless, State Security conducted a security check of all checked-in bags, which required plenty of time before the flight. They opened my bag and held over it a machine that looked and sounded like a giant hair drier with a spotlight on the front of it. God knows what it was looking for, but they didn't seem to find anything. Except a pair of smelly socks and a windscreen chamois that I tried to explain was a towel. Very funny people, these Australians.

Bill Warnock, our Jerusalem representative, was at Tel Aviv airport to meet me. We offered a lift to part of an American consulate family whose driver had not turned up. The roads were clear, but snow drifts a foot deep lay by the roadside.

Bill Warnock, our Jerusalem representative, was at Tel Aviv airport to meet me. We offered a lift to part of an American consulate family whose driver had not turned up. The roads were clear, but snow drifts a foot deep lay by the roadside.

The Archbishop Of Canterbury Is Missing

The next day we were supposed to accompany the Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, to a service at St George's Cathedral. By 11.00 a.m. he had not turned up. We discovered that the Archbishop could not cross into Israel. The bridge at the Jordan was under three feet of water. There was speculation about how they could get him there. Sensible people would have sent a helicopter (I suspect the British embassy suggested this), but only a neutral helicopter would be acceptable to both Israel and Jordan. I didn't happen to have one with me.

We sat in the home of Kamil Nasser, head of the YMCA, waiting for news. The big talk in Jerusalem was the Israeli government's provocative action of arresting twelve alleged conspirators and planning to deport them. One of them was Ghassan Jarrar, the Deputy Director of the Outreach Program of the Beit Sahour Rehabilitation Centre run by the YMCA and supported by World Vision (we visited it the next day). For three years, said Kamil, Jarrar had said nothing which could be considered inciting. "Even to his wife," Kamil joked.

'It is just an excuse', he said. 'Just three days earlier the authorities changed his green card to an orange card. This effectively gave him an absolute clearance to travel between the Occupied Territories and Jerusalem and even overseas if he wanted to.' In order to get this change in card, he must have been given an absolute security clearance; yet three days later he was a security risk worthy of deportation. It was a joke, and a very cynical one.

Fortunately there was more than one way across the Jordan (but only if you were the Archbishop of Canterbury) and he arrived four hours later. The service went ahead then at 2.00 p.m.

The Archbishop Show Goes On

The Archbishop seemed a down-to-earth chap; I thought he'd fit in well at my Doncaster Community Church of Christ, although I sensibly refrained from saying this to him. Jean Penman was present with her chaplain, the Rev Jenny Rockwell. Special seats were reserved for visitors and dignitaries at the front of the congregation, although visiting clergy of bishop rank and above were seated in the choir stalls inside the sanctuary (St George's is a small traditional cathedral with a sanctuary separated from the body of the church by a see-through stone screen). I was seated in the third row of the visitors by the central aisle, so I had a good view.

The processions were impressive. The organ was well played and a young Aussie trumpeter from West End, Brisbane, was on hand to add drama to some of the hymns. They even had a fifteen voice choir. The organist was a European woman who taught music, including pipe organ, to Palestinian children. She played a thrilling Bach Prelude and Fugue as a recessional.

English and Arabic blended in the service and the program read the Arabic way (we would say 'from back to front').

Archbishop Carey preached on Matthew 2, the visit of the Wise Men. He emphasised two words: mission and joy (although only the word joy actually appears in the passage). He said that the Christian faith was about God's mission to the world. 'If human rights are violated, the poor oppressed, the Christian must speak out and take the consequences ... The Christian mission is universal ... to every one.' I remembered that he was speaking in a multi-faith community in which Christians were well outnumbered by Jews and Muslims. 'God's way of evangelising begins with a generosity of spirit that is inclusive. The Wise Men represent the Gentile world. The message is for all people.' I noticed, too, that he never used any name for the land. He talked neither about Israel nor Palestine but referred to 'this land' or 'this Holy Land'. Smart politics.

About joy I remember him saying that there is no joy without pain. He described 'the Jewish people who have passed through so much pain, and still fear', and spoke in a similar vein about the Palestinians. 'Both communities have a right to exist', he said, echoing the moderate line.

Once the Archbishop had been installed as a canon of the cathedral, the local Bishop, Samir Kafity, brought him out into the congregation to pass the peace. But before that he took the opportunity to make a mini-sermon himself I found this very moving. He was a dynamic speaker (even better in Arabic, I sensed) and master of the moment. In the middle of his speech he waved to someone at the back of the church and two Orthodox bishops floated down the aisle. Samir didn't miss a beat but welcomed their late arrival, tying it into what he was saying. Then he commented, 'This is a welcome interruption. Rather better than when Bishop Tutu was here.' On that occasion they had cleared the cathedral during the service because of a bomb threat.

Bishop Samir reminded us that the angels came to a field just a kilometre or two from where we were sitting. I was amazed at this obvious reality. Their message, Kafity said, was two-fold: one, glory to God; two, peace and goodwill towards all people on earth. 'There is only one kind of peace', he thundered. 'There is not two kinds, or three kinds, of peace. There is only one kind of peace. It is a kind in which people are equally honoured.'

For the first time during my two visits to Israel I had a real sense of this being the place where Jesus walked. My earlier visit to Golgotha and other places had an artificial and surreal feel about it.

These sites were no longer what they must have been in Jesus' time. They had become 'churchified' and converted into symbolic places. But to look out across a bare, stony field away to the west and think that one night, 2,000 years ago, a night much like last night, clear, cold, star-filled, a bunch of angels appeared to some shepherds and announced the glory of God and wished peace and goodwill towards all people. I could imagine that happening, and it seemed very real and close.

Bad Media Choices

The next day we were to participate in the dedication of a community centre on the West Bank to the memory of the late Archbishop of Melbourne, David Penman. We met for breakfast on the top floor of the YMCA.

Graeme Irvine, the international president of World Vision, was worried about our video crew arrangements. A naturally modest man, Graeme did not take to the whole television idea with ease. He also thought that taking a television crew into the West Bank sounded a mite foolhardy.

When the crew turned up, all our fears were justified. They arrived in a dark four-wheel drive car festooned with aerials. Two Israeli men peeled out. They were wearing leather jackets and gold-rimmed sunglasses.

Our Palestinian hosts audibly drew breath. One of them whispered in my ear, 'If they go into the West Bank they will be target practice'.

Quietly, we thanked them for their assistance and sent them home.

Jesus Met The Woman At This Well

Although Shechem itself is not mentioned in the New Testament, an important event took place there and it is recorded in John 4. The meeting of Jesus with the Samaritan woman at Jacob's well. It was here that Jesus first revealed to someone that he was the Messiah, and, of course, it was to a Gentile (lest there be any doubts that the Good News is meant for all nations).

So our first stop was at this exact well.

Saint Helena discovered the site in the fourth century. She built a church there which was destroyed by the Persians. A second church was destroyed by somebody else, and a third by an earthquake. At the end of last century a start was made on a fourth, but work ceased on it in 1914 when the walls were, as they were still, about ten feet high. There was no roof.

The well was now underground as other building and the general change in terrain had covered it. Twelve stone steps took us down to a small room which barely contained our party of about forty people. A tiny stone well was in the centre of the room. It was deep, but only wide enough for the bucket to go down. A sanctuary had been built behind it.

Bishop Samir read John 4.

Modern Martyrs

Father Eustinius, the Greek Orthodox priest who acted as warden, told the story of the death of his predecessor, Father Philemonos. In 1971 religious orthodox Jews killed him while he was saying his evening prayers. Armed with axes, they first chopped off his hands, then his genitals. Then they chopped the sign of the cross on his feet and on his bald head. After this they killed him by chopping off his head.

For three years, no-one would come to be warden, then Father Eustinius volunteered. He had an elaborate alarm system set up in the nearby village in case he was attacked. He had needed it. Three times he had been stabbed. Three times bombed. Once attacked with an axe. In all there had been fourteen attempts on his life. The first time he ran after the criminal and caught him; the man confessed to the crime and the courts declared him insane. Six times the priest had appeared in court and each time the person who came to attack the holy site was declared insane.

After telling this story, the priest launched into a vigorous denunciation of the Israeli Occupation and support for Palestinian aspirations. While sympathetic, Bishop Samir finally pointed out that time was moving on, and we were invited to drink from Jacob's well. It was flat, bland, cool and clean, and apparently quite healthy. Unlike Jesus, the water was offered to me in a wine glass!

Built In Three Hours A Day

From here we went to St Luke's. Hospital, where Bishop Samir commented, 'People talk about dialogue between religions and people, but we are living it. We are all Palestinians here, but we are Christian and Muslims living and working together in a common ministry of love and health.'

The new hospital was due to have been finished in 1989, but since the intifada the labourers had only worked three hours a day. The hospital was quite small and a bit drab and old-fashioned, but looked to be effective and well run. Seven thousand in-patients had been dealt with the previous year, sixty-five per cent of them treated free (or nearly so).

Here I met a member of the Palestinian negotiating team. They were supposed to be in Washington but were refusing to go, along with all the Arabs, in protest at the Israeli deportation orders against the twelve Palestinians.

Here I also briefly met Fr Bilal Habiby, the priest of parishes in Nablus and Zebabdeh. A lovely young man from Galilee who trained in Australia under a program set up by David Penman.

Tell the Good News. Use words if necessary.

At the church service which followed in Zebabdeh, Bishop Samir talked about his personal connection with David Penman. David had come to Jerusalem for Samir's enthronement. Samir also spoke of the gifts of Australia to Zebabdeh in Fr Bilal. The gift of a priest and a theological education. During his speech there was a series of sonic booms. The only way I could tell they were sonic booms and not bombs was that no-one else batted an eyelid.

We left the church after the Archbishop preached a fine sermon, finishing with the famous quote from Saint Francis of Assisi, 'Go into the world and preach the Good News. Use words if necessary.'

Right next door to the church was the almost completed David Penman Memorial Clinic. Bishop Samir gave instructions about who should stand on the steps as the official party: he and Archbishop Carey first, Fr Bilal next with Jean Penman, then the Australian Ambassador, then the World Vision people, including 'Paul Hunt'. This was a change; usually they call me 'Peter'. The Bishop announced that Jean would speak, then the Archbishop would pray, then we would have lunch.

Right next door to the church was the almost completed David Penman Memorial Clinic. Bishop Samir gave instructions about who should stand on the steps as the official party: he and Archbishop Carey first, Fr Bilal next with Jean Penman, then the Australian Ambassador, then the World Vision people, including 'Paul Hunt'. This was a change; usually they call me 'Peter'. The Bishop announced that Jean would speak, then the Archbishop would pray, then we would have lunch.

Neither Graeme nor I was bothered that we didn't get to make our speeches. As I said to Graeme later: 'Our speech is a living testament in bricks and mortar. Our speech is the David Penman Memorial Clinic. It is an eloquent speech that will be here long after we are gone. Remember, as Saint Francis said: Tell the Good News. Use words if necessary.

No Holidays At Christmas

We began the next day with the staff in the World Vision office. January 7 was Christmas Day for the Greek Orthodox, but one Orthodox staff member came in anyway. When Bill said how naughty this was, I commented that it was rather typical of World Vision people. Even in Australia dozens of staff and volunteers came in on the night of Christmas Day to answer phones for a television special.

Lying About New Settlements

We drove to Beit Duqu, where I had been before. Last time one young man, Fahad, had walked with a couple of friends over the hills to meet us and have lunch. Fahad was jailed a few weeks later when he helped organise a display at Ibillin of handcrafts from his village, some of which, naturally, included colours representing the Palestinian flag. He was in jail for some months and his case was followed by an Australian journalist who happened to be in Ibillin with Bill at the time.

There was a lively discussion in the house of Fahad's parents, who brought us coffee and biscuits.

'Each visit by James Baker [the US Secretary of State] there is a new Israeli settlement in the Occupied Territories', someone said. I had in fact photographed a new settlement nearby that had been established even while the Madrid talks were going on. Israel's provocative action in scorning world opinion and defying political process on their claims to the Occupied Territories was breathtaking and bemusing.

I asked whether there had been much change in the activity on settlements since I was in the country twenty months before. Yes, they said. There had been many more settlements in the last year, and further land confiscations. Some suggested it was really a way of provoking Palestinians to stop the negotiations.

Land confiscation was in fact advancing even while Israel discussed peace. I was reminded of the Japanese delegation in Washington discussing peace even as the bombers flew across the Pacific towards Pearl Harbour. A smartly dressed, handsome and articulate young man was introduced to me as a lawyer working with a group fighting land confiscations. This seemed futile and ironic to me.

'Surely, if they want the land they will just take it', I suggested. 'It is a military administration and they can do what they want.'

This was true in the end, he explained, but there were ways of fighting it. In 1979 an area of twenty acres near the village was taken 'for military purposes'. In 1989 a new survey was done by the military and an order was issued to confiscate twenty-five acres. But if no objection was lodged the order would automatically extend to 250 acres. This is why the people were lodging objections, because failure to object was a de facto acceptance of the confiscation.

What kind of justice was this? I wondered. Someone makes a claim on my land, and the onus is on me to fight him off. It was the morality of the school yard bully.

Once a confiscation order had been published, the people had forty-five days in which to object. During the Gulf War curfew, some areas of the West Bank were curfewed for fifty days. Confiscation orders continued to be issued, effectively in secret. People under curfew had neither the opportunity to know, nor the opportunity to object.

There was even a plan implying that the whole of the mountain on which this village stood would be confiscated.

The sheik of the village described these things as 'stones [obstacles] on the way to peace'. They suggested to him that the Israelis didn't want peace. In the latest budget, 5,000 new houses were planned for West Bank and Gaza that year. 'They want us Palestinians to negotiate for our rights', he said. 'But why should we negotiate for something which is our right?'

We discussed the responsibility of the whole world for creating the problems in the first place. Graeme said we needed to reawaken the conscience of Britain, the US and others. They must take more seriously their responsibility to find a solution.

The sheik asked for the people of other nations to stand with the Palestinians in the same way they stood with the people of Kuwait. Nothing more, nothing less. One standard, not a double standard. The UN had made resolutions; well, he said, let them be implemented, then let's talk. That was what they said to Saddam Hussein: first implement the resolutions, without negotiations, then we shall negotiate. For Palestinians it was the other way round. Was this justice?

The question was no longer whether there could be justice and only justice. The question now was whether there would be partial justice or a continuation of no justice at all. Then the question was the extent to which the Palestinians would be willing to accept what they saw as partial justice. Of course, from the Israeli side, any erosion of their Occupation would seem like partial justice for them, too. Many were so committed to having the whole of the land that they would feel it an injustice to have less. Whether this was just or not depended on where you sat.

The village had wanted to put in a water system. They had the money and the plans and the labour. They asked permission of the military authorities (ironically called 'The Civil Administration'). The authorities said they would give permission if they could tell the media and invite journalists and TV crews to come to the village to see them sitting with the people, drinking coffee and discussing plans. In other words, they wanted to create a publicity stunt to show how good things were in the Territories. The village refused to prostitute itself in this way. Permission for the water supply was held up for four months.

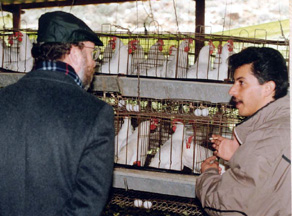

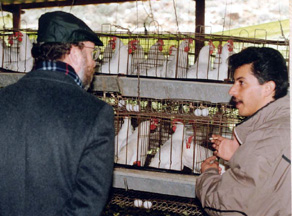

We visited their egg raising project where I was a bit dismayed to see hundreds of hens, two to a cage, being treated as production line fodder for their output. The irony of my dismay was not lost on me or my hosts. I told them how, in Australia, we paid extra for 'free range eggs from free range hens'. 'I wish people would care as much for free range people', someone commented.

We visited their egg raising project where I was a bit dismayed to see hundreds of hens, two to a cage, being treated as production line fodder for their output. The irony of my dismay was not lost on me or my hosts. I told them how, in Australia, we paid extra for 'free range eggs from free range hens'. 'I wish people would care as much for free range people', someone commented.

As we walked towards the village kindergarten, Graeme said, 'This is strategically important for World Vision. We need to stand with oppressed people. Practically, we cannot solve the whole problem of world hunger.' Therefore, he implied, we need to work where we can have most impact for the Kingdom of God.

This was immediately and poignantly reinforced when we met Dema, a little girl of about four with beautiful blond hair and big brown eyes. But behind the angelic face was a tragic story. Dema's father had been in jail for seven months. He still awaited a proper trial. Three times he had been before the courts and each time the judge had postponed the trial to allow the prosecution more time. His little girl had grown a lot in seven months. She played with plasticine and Lego at the local kindergarten while he languished without trial.

Wife Cannot Join Husband

We travelled on to Qubeiba (perhaps the site of Emmaus), where World Vision's photographer, Anwar, lived. Anwar had been married three weeks before to his cousin but because she was from Jordan she was not permitted to come to live with him. Some people in this situation were given permission to reside in the West Bank. Most were not.

Mother Killed By Israeli Soldiers

Anwar's mother had been killed in the massacre at the El-Aqsa mosque, two hours after the shooting had started. Anwar was protecting her when he was struck by a ricochet. Eleven fragments hit him in the back. His mother turned to help him and was shot in the head from almost directly above. Someone, a soldier or a settler, fired from a roof, a wall or a helicopter. Half her face shattered.

Friends carried them both to one gate of the Old City but found a soldier spraying the ground with machine gun fire. They carried them to another gate, found a taxi and set out for a hospital. Near their destination soldiers prevented them from going in, despite seeing the mother's wounds. They continued to another hospital where they were admitted, but it was too late. This hospital ran out of blood and soldiers delayed shipments across town. (Later World Vision helped to establish a blood bank at this hospital.)

At Qubeiba they told us about Ra'ad, aged sixteen (later we met him at the Beit Jala Rehabilitation Centre). Three months earlier at 9.00 p.m. he had been shot just outside Anwar's house. He was walking home from his grandfather's place. It was cold and dark. The soldiers probably saw his shadowy figure and fired. Five bullets entered his legs and pelvis. He limped to his grandfather's house and the soldiers followed him and arrested him, accusing him of wearing a mask (probably it was a scarf). The soldiers brought him back to where they had shot him and beat him, asking him questions. Where had he been? What had he been doing? With whom? After some time they took him to a hospital in Ramallah.

Graeme commented, 'We must call for the protection of these people. This is the first basic thing.'

Harassed For Stuffing Envelopes

We drove Fahad into Jerusalem. He told us the story of trying to get a pass to visit the city so he could help in the World Vision office, stuffing envelopes. After the Gulf War all West Bank people needed permission to travel into Jerusalem. Some had been issued with green identity cards which forbade them entering the city.

To get his permission Fahad put in an application and was told to come to Ramallah for an interview. He arrived at 9.00 a.m. for his 9.30 appointment. At 2.00 p.m. the secret police interviewed him. They asked him about his village: Who were the leaders? Who were the trouble makers? Who were the ones who made decisions? Fahad claimed to be ignorant of such matters, although anyone in the village could have answered. The policeman resorted to bullying and intimidation. 'I could arrest you right now and throw you into jail', he threatened. 'If I have done something wrong, I should be arrested', said Fahad. 'No. When I arrest you I want to come in the night so I can see the look in your mother's eyes.'

All this to get permission to travel seventeen kilometres to stuff envelopes.

Christmas In January

We arrived a little late at the Bethlehem Arab Society for Rehabilitation. For me, a return visit. It was an impressive institution, beautifully designed and built to a high international standard. The colours were bright, the care obviously full of compassion. I could imagine how welcoming it would be to a paraplegic who had been stuck at home wondering whether life was worth living.

Some who had visited the Society had felt the quality of the facility inappropriate for the West Bank. What an irony. Surely the poor deserve the best. If this can be justified anywhere, it can surely be justified amid the squalor and wretchedness of life under occupation.

Edmund Shehader, the director, was an urbane, sophisticated, upper class Palestinian. From an old Bethlehem family, he lived in a century-old manor overlooking Bethlehem and drove an old Mercedes. In Melbourne he would overlook the sea at Brighton and drive a brand new Merc. His salary would be astronomical. Here he stood out as a rich fish in a poor pond, yet his annual salary was the equivalent of just A$25,000. Ten years after he had started to work for the Bethlehem Arab Society, his salary was still much less than in his old job.

Edmund and his wife, Hilda, entertained us for lunch with his twelve-year-old son and twenty-four-year-old niece, recently returned from studying in America. It was Orthodox Christmas, and I realised that we were invading their home for Christmas dinner. How gracious and welcoming they were to us. And what a feast they shared with us. There was a sense of how pleasant life must have been. And how pleasant it might yet be again, for those Palestinians who had the opportunity to make the most of their skills and resources.

Edmund and his wife, Hilda, entertained us for lunch with his twelve-year-old son and twenty-four-year-old niece, recently returned from studying in America. It was Orthodox Christmas, and I realised that we were invading their home for Christmas dinner. How gracious and welcoming they were to us. And what a feast they shared with us. There was a sense of how pleasant life must have been. And how pleasant it might yet be again, for those Palestinians who had the opportunity to make the most of their skills and resources.

The centre struggled to find its running costs. It got no tax breaks from the Israeli government: it paid taxes just like a business and received not one shekel of support in return. Similar Israeli institutions in Israel received substantial government funding.

Around 4.00 p.m. we arrived at the Beit Sahour YMCA Rehabilitation Centre which concentrated on psychological and vocational counselling for the intifada victims.

Akram had been studying at Hebron University in comparative religion. One night at 9.00 p.m. he was jogging near an Israeli settlement when a settler shot him three times. He was taken to hospital in Israel where he had six operations in six weeks. They wanted to charge him US$40,000 for his treatment. Then he was shunted around a few hospitals and finally taken to Jordan for rehabilitation.

Akram was not a major participant in any intifada action at the time of his shooting. The settler who shot him said he did so because he thought Akram was going to pick up a stone. The settler is not in jail.

Akram was an easy target. Leila, a Palestinian woman who was the senior counsellor at the Centre, said that most of the people they treated were not involved at the time in stone throwing. 'In any case', someone chipped in, 'there is a principle of proportionality, isn't there? Of course, we know that people throw stones. Maybe they should, may they should not. But do you fire bullets at a child who throws stones? There is a question of whether the response is in proportion to the crime.'

Boy Given A Grenade

Majid was another victim. A twelve-year-old shepherd boy in a town near Zebabdeh, he went through the rocky side of the mountain to home after curfew one night. He heard a noise, went to see and found soldiers. One soldier called out to him so he went down. 'Do you want a drink?' asked the soldier. He seemed friendly. 'No.' 'Are you hungry?' 'No.' The soldier left and he turned away. The soldier threw something. He picked it up; he didn't know what it was and it was dark. The thing exploded.

Majid was another victim. A twelve-year-old shepherd boy in a town near Zebabdeh, he went through the rocky side of the mountain to home after curfew one night. He heard a noise, went to see and found soldiers. One soldier called out to him so he went down. 'Do you want a drink?' asked the soldier. He seemed friendly. 'No.' 'Are you hungry?' 'No.' The soldier left and he turned away. The soldier threw something. He picked it up; he didn't know what it was and it was dark. The thing exploded.

The incendiary grenade burned Majid's entire body. His face had been restored by superb plastic surgery. His hands and neck remained scarred.

Recovery Is Painful and Forever

Leila, who held a Master's degree in education and psychology from the USA, talked about post-traumatic stress disorders. People bad flashbacks, extreme depression and anxiety. For two to three years after their injury they often did nothing. They slept late, perhaps only getting up if their friends came around. They fought with their families, broke things, had anger fits and then regrets that left them wondering whether they were going crazy. Intifada victims were at first treated like heroes, and they had to act out their roles. They could not easily show anger or sorrow over their injuries.

The Centre would tell them this was all normal and common for people who had experienced trauma. The therapy was to help them to see what they had not lost. To be assertive and to say what they could do, preventing others from making them dependent. People realised they were not crazy. They were helped to improve their communications skills.

The Beit Sahour Centre was located on the Field of the Shepherds. This is the place (although there were two other nearby sites claimed) where the angels came to announce God's glory and peace and goodwill to all people. How lovely that a Christian ministry of restoration and hope operated now from this field.

Three hours later a group of Israeli soldiers, with guns drawn, surrounded the Centre, entered the premises and began searching and interviewing those present. On one patient they discovered a small piece of paper with the word Fatah written on it. The soldiers took him away.

Serbians Cannot Forgive Either

The next day, 8 January, was another strike day. Bill rang at 10.00 a.m. to ask whether it was all right to take an Australian sponsor to Ramallah to visit her sponsored child. The way he said it made it sound as though he wasn't sure it was a good idea, but I wasn't going to say no to a customer.

Sixty-seven-year-old Luba Relic was a special sponsor and well known to many in the Donor Service Team for New South Wales. The sponsor of ten children, she worked at the Menzies Hotel in Sydney for more than twenty years after coming to Australia from Yugoslavia in 1949. Remarkably loquacious, we discovered that Luba could recount whole slabs of European and Middle Eastern history, especially if it involved the Greek Orthodox Church of which she was a deeply committed adherent. She was a lady with an amazing faith, confident of God's protection to the point of foolhardiness. Determined and stubborn, she also tended to be short to the point of rudeness.

Sixty-seven-year-old Luba Relic was a special sponsor and well known to many in the Donor Service Team for New South Wales. The sponsor of ten children, she worked at the Menzies Hotel in Sydney for more than twenty years after coming to Australia from Yugoslavia in 1949. Remarkably loquacious, we discovered that Luba could recount whole slabs of European and Middle Eastern history, especially if it involved the Greek Orthodox Church of which she was a deeply committed adherent. She was a lady with an amazing faith, confident of God's protection to the point of foolhardiness. Determined and stubborn, she also tended to be short to the point of rudeness.

Our first problem was that we could not take Bill's car with its Jerusalem plates. The solution was to find a West Bank taxi which would take us to Ramallah. Ramsey from the office went down to find a car and driver. The only one available had Jerusalem plates, but the driver thought it would be OK. 'Things are not so bad for taxis in Ramallah', he said. Ramsey actually knew the driver and it turned out that Bill had known his father and brother for more than four years. In the end he stayed the whole day with us, visiting the school and the family of the sponsored child and helping us to translate.

Luba's personal story was profoundly moving. Towards the end of the War she was twenty-one years old and living in Yugoslavia. She was married for about a year when her husband ('He called me a princess') was killed by the Germans in an ambush. Her daughter had just been born, but her husband had never seen her.

Luba was a Serb. After almost fifty years she still seemed unable to forgive the atrocities committed by Croatians against the Serbians. She talked about how the Croatians 'killed the mothers and children and threw them in the river to float up to Belgrade'. Later, when Bill mentioned an Israeli group that was helping the Palestinians and commented that not all Israelis were bad people, she said, 'The Croatians are all bad. They are Ustashi, every one. It is bred into them.'

Here, I thought, was the post-traumatic stress syndrome. Some acts of atrocity are so grave that people can only continue to live if they demonise those who commit the atrocity. Only an evil people could do what Luba knew had been done by some Croats to some Serbians. In Palestine there were many for whom the pain of the occupation could only make sense if they believed all Israelis were the devil incarnate. Such deeply held prejudice was hard to dig out and change.

Luba's Story

What caused this kind of prejudice in Luba's life? The Croats forced her brother to dig a grave into which were thrown the bodies of Germans and her own grandmother. But her grandmother was not dead. When her grandmother cried out they hit her on the head with a shovel. Then they forced the grandfather to fill in the grave, burying his wife alive. Who could live with such a memory?

Soon after, Luba learned her husband was dead. She collapsed and was in a coma for five weeks. The nurses pumped milk from her breasts for her baby girl, but the child grew progressively weaker and then contracted pneumonia. When Luba came to, her little daughter was under one kilogram in weight and near death. Luba did not want to see her, but the nurses brought her anyway. They thought she would die soon. Luba was afraid, but once in her mother's arms the baby smiled, and Luba prayed for God's forgiveness that she had rejected the child.

Within a few days Luba was well enough to leave the hospital, but the prognosis for her daughter was grim. One day walking to the hospital Luba slipped on the icy footpath and fell to her knees, hurting herself. Angry at one more experience of pain, she looked up to the sky and said, 'God, what more do you want to take from me?'

Suddenly there was a bright light. Luba felt that the light came into her body and filled her. She didn't know what was happening to her or what the light was, but she knew she was being filled with the Spirit of God. In that same moment she knew her daughter had been healed.

At the hospital she saw the doctor and he smiled as he turned to face her. 'It's a miracle', he said. 'I know', Luba replied.

Later Luba saw an advertisement for immigration to Australia. She went to apply but the official asked, 'Where is your husband?' Only married couples were being accepted for immigration, and especially not widows with a dependent child.

Luba was disappointed and upset. Seeing her distress, the senior Australian immigration official, a man named Billie Sneddon, who would later be Speaker of the House of Representatives in the Australian Parliament, invited her into his office. She told the story of her circumstances and he was choked with tears. He ordered the officials to speed up her case despite the policy, and three days later she was on her way to Australia.

Finding Luba's Sponsored Children

Luba  sponsored Rameez at the Ramallah Evangelical Boys' Home, run by Audeh and Patricia Rantisi. On arrival we discovered that we would have to go on to Beir Zeit if we wanted to see Rameez. Owing to the strike, no-one was yet at the school, and there was no communication. Taking the boy's name, we headed off to Beir Zeit and stopped the first man we saw in the village. He climbed into the car to direct us. Sure enough, in a town of 15,000 people it wasn't hard to find.

sponsored Rameez at the Ramallah Evangelical Boys' Home, run by Audeh and Patricia Rantisi. On arrival we discovered that we would have to go on to Beir Zeit if we wanted to see Rameez. Owing to the strike, no-one was yet at the school, and there was no communication. Taking the boy's name, we headed off to Beir Zeit and stopped the first man we saw in the village. He climbed into the car to direct us. Sure enough, in a town of 15,000 people it wasn't hard to find.

More surprisingly, we discovered that they had been accepted into Australia's immigration program. Rameez' s mother had two sisters in Sydney. On Saturday they would fly to Amman, get their papers from the Australian embassy there, and then fly on to Australia by the end of January.

Revisiting The Holocaust

Next morning I visited Yad Vashem, a large memorial to the Holocaust. It was impressive and moving. I found it incredible that such a thing could happen and that it could be done by thinking human beings. And the world stood by, probably because of a combination of ignorance and disbelief.

The memorial left me with the impression, perhaps unintended, that the Jews were the only ones to suffer at the hands of the Nazis. But many others, also running to millions, were their victims. Homosexuals, communists and many whose main crime was their potential danger to the Nazis themselves.

The first part of the display concerned the rise of Nazism and discrimination against Jews in Germany. But what struck me were the many parallels with the present activities of Israel against the Palestinians. It amazed me this was not obvious to more Israelis. The very first panel stated 'an underlying element of the Jewish Tragedy was their fundamental powerlessness, as an isolated people bereft of a sovereign state, in the face of the Nazi onslaught'. One may have equally said, 'an underlying element of the Palestinian problem was their fundamental powerlessness, as an isolated people bereft of a sovereign state, in the face of the Israeli onslaught'.

Among actions taken against Jews in the early days were the Reich Citizenship Laws, which meant that only people who were of the Aryan race could be citizens. These laws 'reduced Jews to being second-class citizens'. Again the parallel hit me. Palestinians are second-class citizens, on the basis that only people of the Jewish faith could be full citizens of Israel. Of course, the German laws went further than Israeli law; but the Germans confiscated Jews' property, and this was also happening to Palestinians every day in Israel and the Occupied Territories. People were arrested on flimsy excuses, and administrative obstacles of all kinds were placed in their path. Reading the list off the boards was like reading a list of present activities in the Occupied Territories.

Of course, in Germany it got much worse. I could not believe it would here, but then one had to reflect on history and say that few would have believed that the actions against the Jews could have been possible in a modern, sophisticated and liberal state like Germany in the 1930s.

Here was the modern dilemma: How could a nation which had endured all this allow the actions being taken against Palestinians to continue, let alone be responsible for them?

Human nature is very strange.

next chapter - "happy birthday in Cambodia"

next chapter - "happy birthday in Cambodia"

Bill Warnock, our Jerusalem representative, was at Tel Aviv airport to meet me. We offered a lift to part of an American consulate family whose driver had not turned up. The roads were clear, but snow drifts a foot deep lay by the roadside.

Bill Warnock, our Jerusalem representative, was at Tel Aviv airport to meet me. We offered a lift to part of an American consulate family whose driver had not turned up. The roads were clear, but snow drifts a foot deep lay by the roadside. Right next door to the church was the almost completed David Penman Memorial Clinic. Bishop Samir gave instructions about who should stand on the steps as the official party: he and Archbishop Carey first, Fr Bilal next with Jean Penman, then the Australian Ambassador, then the World Vision people, including 'Paul Hunt'. This was a change; usually they call me 'Peter'. The Bishop announced that Jean would speak, then the Archbishop would pray, then we would have lunch.

Right next door to the church was the almost completed David Penman Memorial Clinic. Bishop Samir gave instructions about who should stand on the steps as the official party: he and Archbishop Carey first, Fr Bilal next with Jean Penman, then the Australian Ambassador, then the World Vision people, including 'Paul Hunt'. This was a change; usually they call me 'Peter'. The Bishop announced that Jean would speak, then the Archbishop would pray, then we would have lunch. We visited their egg raising project where I was a bit dismayed to see hundreds of hens, two to a cage, being treated as production line fodder for their output. The irony of my dismay was not lost on me or my hosts. I told them how, in Australia, we paid extra for 'free range eggs from free range hens'. 'I wish people would care as much for free range people', someone commented.

We visited their egg raising project where I was a bit dismayed to see hundreds of hens, two to a cage, being treated as production line fodder for their output. The irony of my dismay was not lost on me or my hosts. I told them how, in Australia, we paid extra for 'free range eggs from free range hens'. 'I wish people would care as much for free range people', someone commented. Edmund and his wife, Hilda, entertained us for lunch with his twelve-year-old son and twenty-four-year-old niece, recently returned from studying in America. It was Orthodox Christmas, and I realised that we were invading their home for Christmas dinner. How gracious and welcoming they were to us. And what a feast they shared with us. There was a sense of how pleasant life must have been. And how pleasant it might yet be again, for those Palestinians who had the opportunity to make the most of their skills and resources.

Edmund and his wife, Hilda, entertained us for lunch with his twelve-year-old son and twenty-four-year-old niece, recently returned from studying in America. It was Orthodox Christmas, and I realised that we were invading their home for Christmas dinner. How gracious and welcoming they were to us. And what a feast they shared with us. There was a sense of how pleasant life must have been. And how pleasant it might yet be again, for those Palestinians who had the opportunity to make the most of their skills and resources. Majid was another victim. A twelve-year-old shepherd boy in a town near Zebabdeh, he went through the rocky side of the mountain to home after curfew one night. He heard a noise, went to see and found soldiers. One soldier called out to him so he went down. 'Do you want a drink?' asked the soldier. He seemed friendly. 'No.' 'Are you hungry?' 'No.' The soldier left and he turned away. The soldier threw something. He picked it up; he didn't know what it was and it was dark. The thing exploded.

Majid was another victim. A twelve-year-old shepherd boy in a town near Zebabdeh, he went through the rocky side of the mountain to home after curfew one night. He heard a noise, went to see and found soldiers. One soldier called out to him so he went down. 'Do you want a drink?' asked the soldier. He seemed friendly. 'No.' 'Are you hungry?' 'No.' The soldier left and he turned away. The soldier threw something. He picked it up; he didn't know what it was and it was dark. The thing exploded. Sixty-seven-year-old Luba Relic was a special sponsor and well known to many in the Donor Service Team for New South Wales. The sponsor of ten children, she worked at the Menzies Hotel in Sydney for more than twenty years after coming to Australia from Yugoslavia in 1949. Remarkably loquacious, we discovered that Luba could recount whole slabs of European and Middle Eastern history, especially if it involved the Greek Orthodox Church of which she was a deeply committed adherent. She was a lady with an amazing faith, confident of God's protection to the point of foolhardiness. Determined and stubborn, she also tended to be short to the point of rudeness.

Sixty-seven-year-old Luba Relic was a special sponsor and well known to many in the Donor Service Team for New South Wales. The sponsor of ten children, she worked at the Menzies Hotel in Sydney for more than twenty years after coming to Australia from Yugoslavia in 1949. Remarkably loquacious, we discovered that Luba could recount whole slabs of European and Middle Eastern history, especially if it involved the Greek Orthodox Church of which she was a deeply committed adherent. She was a lady with an amazing faith, confident of God's protection to the point of foolhardiness. Determined and stubborn, she also tended to be short to the point of rudeness. sponsored Rameez at the Ramallah Evangelical Boys' Home, run by Audeh and Patricia Rantisi. On arrival we discovered that we would have to go on to Beir Zeit if we wanted to see Rameez. Owing to the strike, no-one was yet at the school, and there was no communication. Taking the boy's name, we headed off to Beir Zeit and stopped the first man we saw in the village. He climbed into the car to direct us. Sure enough, in a town of 15,000 people it wasn't hard to find.

sponsored Rameez at the Ramallah Evangelical Boys' Home, run by Audeh and Patricia Rantisi. On arrival we discovered that we would have to go on to Beir Zeit if we wanted to see Rameez. Owing to the strike, no-one was yet at the school, and there was no communication. Taking the boy's name, we headed off to Beir Zeit and stopped the first man we saw in the village. He climbed into the car to direct us. Sure enough, in a town of 15,000 people it wasn't hard to find.