China 1991

In 1991 I visited Beijing for the second time. I was part of a small group with the president of World Vision International, Graeme Irvine. I was included in the party because of involvement over many years with World Vision's work in Hong Kong, and more particularly because I had been part of an initial survey team which had designed World Vision's response to serious flooding earlier that year in An Hui province.

The visit impressed on me the complexity of revolution. First, Beijing itself had changed physically in the nine years since my previous visit. We had then stayed in a lovely old, rambling guest house surrounding a beautiful Chinese garden. Now we were in a tall glass international hotel run by a Swiss-trained Singaporean.

Second, I was surprised at the frankness of some of our discussions. In formal situations, China's position might be clear and consistent. But informal conversations revealed other streams of belief and action. Perhaps I had thought that the tanks crushing the student protest would have crushed all comment. I discovered that dreams and aspirations are tenacious and enduring.

Hiding the Marks of the Martyrs

They were flying kites in Tiananmen Square. Mary Cheung, World Vision's communications director in Hong Kong, said, 'They're very symbolic. The people fly them because they have an appearance of freedom but they're still attached to the ground by strings.'

This day in Tiananmen Square the young official accompanying us, tall, in his twenties, said, 'This is the place to take a photo because it is the place of the martyrs'. We were standing in front of the memorial column to the martyrs of the Communist Revolution, but he had more recent martyrs in mind. The ones who had used this statue as the centre for a peaceful youth protest that ended on the night of 4 June.

When I didn't get the point he indicated that this was the place where 'we had gathered'.

I asked him if he had been here on the night the tanks came. He said, 'No. If I had been here on that night I would be in jail now'. As we walked away from the Square he said, 'Change will come in China but now we just have to be patient'.

David Ngai, the executive director of World Vision Hong Kong, pointed out the place where the steps of the martyrs' memorial had been replaced. The new stone obscured the damage done by the tanks which had driven up the steps.

Beijing Changes Fast

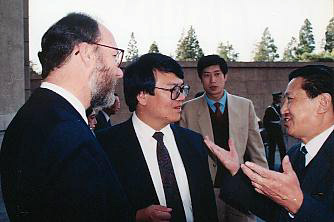

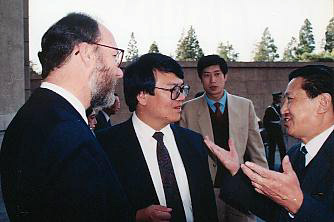

I had last been in the Chinese capital nine years earlier in 1982, when I also accompanied another World Vision president, Stan Mooneyham. It was his last official duty before finishing with World Vision. I recalled how impressed I was with the way the Spirit moved to create friendship between Dr Mooneyham and the officials.

On this second visit I met one man who was in that earlier series of dinners. I think I can find his face in the photographs taken then —Mr Zhu. We greeted each other as old friends. Being an 'old friend' in China was a special honour.

On this second visit I met one man who was in that earlier series of dinners. I think I can find his face in the photographs taken then —Mr Zhu. We greeted each other as old friends. Being an 'old friend' in China was a special honour.

Since I was first in Beijing a lot had changed. Most noticeable was the number of high-rise buildings, especially hotels. There was no suitable international hotel in 1982; now there were dozens.

Fashion had changed in the streets too. People were wearing all sorts of clothes, with both young men and young women smartly dressed. In the old days it was just the Mao suit, grey, green or dark blue. Now there were many colours.

The mood too may have changed, although I could not recollect very strongly what the mood had been nine years before. Certainly people didn't discuss events outside China then. You didn't have frank discussions like the one we had in Tiananmen Square that day. So many people were speaking openly about change now. I felt that the Chinese leadership was quite out of touch with the mass of public opinion. Ordinary people were just being patient, waiting for change to come.

Aussies Are The Best. Chinese, the Most Polite.

One of our hosts, Mr Jiang, described the different nationalities he worked with. 'The Australians were number one', he said, 'open and easy to make friends.' Of course he would say that to us.

'The Americans are too talkative', he opined. 'They just say "Hello, hello", "How are you?" and "Goodbye" and act like big brothers.' The English and New Zealanders were too formal: 'High-nosed people'. The Germans were friendly with a sense of humour: 'Very demanding but fair'.

The Chinese are renowned for indirection. Straight answers, for which Australians tend to be unfairly well known, are not part of their make-up. I think the most frightening way to begin a sentence in an official meeting in China is with the words 'Speaking frankly.'

Much of our official discussion with the Chinese concerned World Vision's earlier response to a flood in An Hui province. The United States contribution to An Hui was only $25,000, this being the Ambassador's limit. At many millions, World Vision's contribution was the biggest international response.

Graeme Irvine pointed out that 'World Vision is a small agency'. Madam Wu of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said, 'We don't judge a hero by his size'.

Contrasting Beijing With Moscow.

Beijing was a beautiful city, reminiscent of Paris and Melbourne. Very wide, tree lined streets. Quite modern. Bicycles everywhere. A lot of vitality and a sense of progress.

Graeme contrasted Beijing with Moscow. In Moscow nothing worked. There were no products in the shops. You could not make international phone calls easily. Faxes did not arrive. The hotel plumbing was ineffective. The laundry service did not work. There was no food. Moscow was very drab, Graeme said.

Beijing by comparison was full of life. People apparently had more freedoms — there was a more free feeling even than in Singapore.

Pragmatism Before Idealism.

The national strategy was to put economic before political reform. The open policy to the West continued, and openness to restructuring the economic side of Chinese life continued too. One had to say that the Chinese were taking a pragmatic approach.

Of course, issues of political reform were not being dealt with by us, and issues of human rights were definitely not on our host's agenda.

We noted that people who were formerly in the progressive reform area of politics were now beginning to emerge again in lower positions. They had been demoted but one suspected they were on their way back. At least this was better than in the old days, when such people would have lost their lives or been put in jail.

Again we saw there was a great deal of hope for reform as long as people were patient.

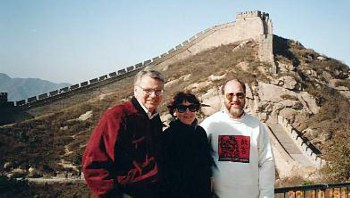

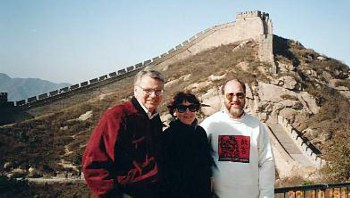

Ming Tombs and the Great Wall of China.

For one day of our visit we were treated as official tourists, just as we had been a decade before.

The Great Wall and the Ming Tombs had changed quite a lot. Nine years previously one could simply drive up to the Great Wall and start walking. Now it cost money.

The Great Wall and the Ming Tombs had changed quite a lot. Nine years previously one could simply drive up to the Great Wall and start walking. Now it cost money.

They had built a cable car which you could ride for A$5 When you got to the top, you had to pay another few dollars to walk along the Wall. Locals paid much less.

The real price was in pain. The walk was unremittingly downhill. By the time we entered the tourist market at the base of the Wall, our knees were in serious decline.

The Ming Tombs were now the same kind of commercial corner. It cost a few cents to enter the park, but a few dollars to go down into the Tomb. While the admission charges were very low by international standards, it was an indication that the Chinese were doing their best to make the most of the tourist trade.

next chapter - "would I be any different?"

On this second visit I met one man who was in that earlier series of dinners. I think I can find his face in the photographs taken then —Mr Zhu. We greeted each other as old friends. Being an 'old friend' in China was a special honour.

On this second visit I met one man who was in that earlier series of dinners. I think I can find his face in the photographs taken then —Mr Zhu. We greeted each other as old friends. Being an 'old friend' in China was a special honour. The Great Wall and the Ming Tombs had changed quite a lot. Nine years previously one could simply drive up to the Great Wall and start walking. Now it cost money.

The Great Wall and the Ming Tombs had changed quite a lot. Nine years previously one could simply drive up to the Great Wall and start walking. Now it cost money.