Ethiopia 1991

I had discovered in the southern Sudan that war is the enemy of development. Now, in Tigray, Ethiopia, I discovered the corollary — that peace is fertile ground for the explosive blossoming of people and abundant life Nevertheless, war and its belief system that destroyed the value of human life left a legacy of robbery and violence that one encountered every day. Sometimes the events were trivial: a small robbery or a careless attitude. Occasionally the events were more dangerous: a resort to violence or the use of a weapon to achieve power over someone.

Much of my thinking over a decade about the complexity of aid was focussed in the story of one little girl, Selamawit. Seven factors were operating in a complex way that were killing her.

Addis Ababa is a Safe Town. NOT.

People in Ethiopia were more relaxed than when I'd visited it once before, when Mengistu was still in power. I got a visa at the airport without any official paperwork when the local World Vision office mistook my arrival time. Yemane, our Ethiopia director, thought this remarkable. Another Australian colleague had been made to wait three hours because the paperwork had not arrived on time.

The statue of Lenin outside the Hilton was gone. Children had attempted to demolish it and succeeded with the help of heavy machinery.

The Ethiopian Airlines in-flight magazine said, 'Addis Ababa is a safe city. You can walk safely at night.' They were dreaming. You couldn't walk alone any time. Two thieves robbed a Canadian colleague Philip Maher one morning by the push-shove-and-frisk routine while he was walking with four others on the way to church from the Ghion Hotel. Our cameraman, Doug, received the same treatment in the early evening darkness walking between the Ghion and the Hilton, but spun around, scaring them off. My baseball cap was stolen off my head while I sat in the car in a traffic jam with the window down.

Yemane said that sometimes in the markets (which we had just walked through) someone came along behind people with nice shoes, got them in a bear hug and lifted them off the ground while an accomplice stole their shoes. I checked to see if I was still wearing my Reeboks.

Bottoms Up in Tigray

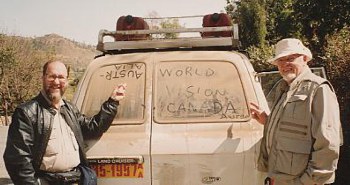

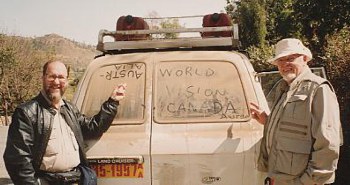

I was in Ethiopia accompanying a World Vision Canada film team. My goal was to do some television segments that we would use in our World Vision Australia television programs. I also wanted to assess the opportunity for project work in Tigray.

I was in Ethiopia accompanying a World Vision Canada film team. My goal was to do some television segments that we would use in our World Vision Australia television programs. I also wanted to assess the opportunity for project work in Tigray.

On the flight up to Tigray, as we looked over a landscape of wiggly worm trails, Yemane talked about Ansokia in the height of the famine. (Ansokia Valley was an area featured in the BBC report that exposed the world to the terrible Ethiopian famine in the middle l980s. World Vision began an extensive program there, and for a time Yemane was its senior manager.) He recalled how the Tigray People's Liberation Force had once killed three staff when they mistook them for government officials. The World Vision compound was next door to a club for party officials. When it was attacked some ran away, and the pursuing freedom fighters thought the people in our compound were the escapees.

Life had been difficult in Ansokia. Many were dying of starvation, and doctors and nurses were making life and death decisions about who to feed and who to leave to die. There was constant insecurity.

The day before we had spoken to the director of REST, the aptly acronymed Relief Society of Tigray. Tigray had been ignored for a generation, he said, but now the people had high expectations. War had ended and the Tigreans had won. They expected help. But out of 900 million birr requested for Wollo and Tigray, the Ethiopian government could only find B 100—150 million. And Tigray would get only thirty. It needed 500.

Many people saw the war as a way to bring social change, not just peace. If those expectations were not met, maybe the peace would be destabilised. His implied message was: If World Vision believes in peace, you will bring aid to Tigray.

He was very conscious of dependency problems. Handouts must be accompanied by education. 'The process in Tigray is very bottom up,' he said.

Putting Up A Good Front

We landed in Mekelle and two Toyota Land Cruisers took us to the Abraha Atsebeha Hotel. Resembling an eighteenth century English manor house, it was all front. Little in the hotel was working although the flat bread was tasty and the spaghetti nourishing. We thanked the Italians for this edible legacy.

We landed in Mekelle and two Toyota Land Cruisers took us to the Abraha Atsebeha Hotel. Resembling an eighteenth century English manor house, it was all front. Little in the hotel was working although the flat bread was tasty and the spaghetti nourishing. We thanked the Italians for this edible legacy.

I have never been too fussy about where I stay as long as it's clean. And as long as there's a working toilet. And as long as there's hot water for the shower, or at least lukewarm.

The hotel was at least clean. So, one out of three. I shared a toilet and bathroom with guests from five other rooms; the toilet overflowed and stank. The drizzle of water in the shower seemed to have come from a glacial cave far removed from the mildness of the equatorial Tigrean plateau. As usual, I cleaned my teeth in Ambo water, the excellent Ethiopian mineral water with bubbles that last three days. Splashing on plenty of cologne felt like covering a multitude of sins.

My logic told me that my discomfort at the lack of creature comforts was nothing compared to millions in the world who lived their whole lives without a hot shower. When a call of nature comes at four in the morning, and the only option is a stuffed loo, emotion takes over from logic.

Moonscape

My little troubles were soon forgotten, however, as we drove into the countryside. A desolate, sparsely treed landscape. Shale and rocks abound.

Once there were trees and a river,

Once there were trees and a river,

Once there was grass where you stand,

Once there were songs, about rights instead of wrongs,

Once was the time of man.

We were looking at a humanly-engineered environmental disaster.

Patients in the Dirt

Two hours drive north of Mekelle we arrived in the town of Wukro. The hospital there was unlike any you would find in Australia: it had earth floors, no furniture and people were lying on the floor in the dirt. The staff were too stretched to do a baseline nutrition survey. They could only react to patients as they presented themselves.

I was bothered by an unfamiliar smell. Hospitals usually smell of disinfectant. This was the musty, sickly smell of unwashed bodies and blankets. There was no water in this town. Any water they could find was not for washing.

Seven Things to kill a little Girl

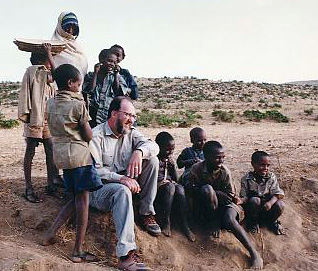

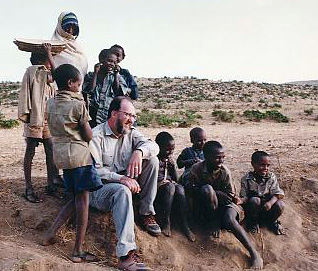

The staff introduced me to a little sick girl. Her name was Selamawit. She was two years old and weighed just five kilograms. What was the problem?

In Wukro malaria was an epidemic. In the previous two months in Selamawit's village of 800 people, 147 had died — 137 under fourteen. At first glance, then, I came to the quick conclusion that Selamawit's problem was malaria.

It was not that simple.

Selamawit might yet survive the malaria if she hadn't been so weak. And she was weak from malnutrition. So the problem was malaria on top of malnutrition.

Proper food was in such short supply that even in the hospital there was no milk for the child patients, only bread and tea. The nurse said that without proper food Selamawit had no chance of surviving the malaria. We offered to buy milk for Selamawit and the three other under-fives in the clinic. The nurse said it is 'very expensive' — A$1.55 per litre. We left A$190 for milk for four children for a month (one litre a day).

So the problem was malaria on top of malnutrition. There were two factors working interdependently. Right?

Again, it was not that simple.

The reason there was no food was war. War had prevented the family from farming. They had run away for their own safety, becoming refugees in a place 200 kilometres away from home. Now they had returned, but after the short rainy season. And if you didn't get your crops in before the rains, you must wait another whole year for the next chance. So no harvest that year.

Malaria, on top of malnutrition caused by war and seasonal rains. Four factors conspiring to threaten Selamawit's existence.

Well, it was not that simple either.

Less than 100 years ago, so the older men and women told me, this area of Ethiopia was covered by forests. Now it was a desert with barely a tree from one long horizon to another. In two or three generations, every tree had been cut down. As the trees were taken away, the water table sank. Crop yields plummeted. Grandfathers talked of harvests big enough to feed a family for a year or more. Now they harvested enough for a week. And for fifty-one weeks of the year they were dependent on food aid.

So the problems were malaria, on top of malnutrition caused by war, seasonal rains and environmental destruction. Five factors that would kill Selamawit.

Sorry, it was not even that simple.

I began to ask questions like these: Who owns the land? How is produce marketed? Who makes the profits? The answers revealed a slowly changing political and economic system that had been weighted against the farmer and in favour of the mythical State. The residues of communism, African style.

Malaria, malnutrition, war, seasonal rains, environmental destruction, bad politics and economic structures tilted unjustly against the poor: seven factors that would kill Selamawit.

Can We Eliminate Poverty? Yes, We Can

Can We Eliminate Poverty? Yes, We Can

During the day, someone said that the problems seemed too huge. 'No', I replied, 'we just need a sense of proportion. There's lots of money around, if we only want to spend it on the things that will make a difference. World Vision — and the world — needs a sense of proportion on a range of things.'

Someone worked out that the poverty problems of the world could be solved if less than thirty billion dollars a year were spent on the right things. In 1992, more than 300 billion dollars were spent by the United States, the European Community and Japan simply protecting their own farmers from competition.

If we wanted to solve the problems of poverty, we could not use the excuse that the world did not have the resources. The world simply lacked the leadership with the willpower.

next chapter - "Flying a kite"

I was in Ethiopia accompanying a World Vision Canada film team. My goal was to do some television segments that we would use in our World Vision Australia television programs. I also wanted to assess the opportunity for project work in Tigray.

I was in Ethiopia accompanying a World Vision Canada film team. My goal was to do some television segments that we would use in our World Vision Australia television programs. I also wanted to assess the opportunity for project work in Tigray. We landed in Mekelle and two Toyota Land Cruisers took us to the Abraha Atsebeha Hotel. Resembling an eighteenth century English manor house, it was all front. Little in the hotel was working although the flat bread was tasty and the spaghetti nourishing. We thanked the Italians for this edible legacy.

We landed in Mekelle and two Toyota Land Cruisers took us to the Abraha Atsebeha Hotel. Resembling an eighteenth century English manor house, it was all front. Little in the hotel was working although the flat bread was tasty and the spaghetti nourishing. We thanked the Italians for this edible legacy. Once there were trees and a river,

Once there were trees and a river, Can We Eliminate Poverty? Yes, We Can

Can We Eliminate Poverty? Yes, We Can