Guatemala 1990

Earlier in Sri Lanka I had seen how it might be possible for World Vision to work in such a way that our development processes took the whole complex world into account. Not a piecemeal approach of bits and pieces, but a comprehensive process that honoured the wisdom and ability of the local people. With some colleagues, I began to talk these ideas up. One World Vision office which responded with enthusiasm was Guatemala and its director, Dr Annette de Fortin. In my heart, new hope began to emerge that World Vision's work would be increasingly effective and empowering of people.

Headaches in Guatemala

My head ached. The altimeter in the Toyota Land Cruiser said 3,000 metres. Higher than Kosciusko. Up here it took at least two days to acclimatise. Any kind of activity left me breathless.

Geoff Renner, my World Vision colleague from Melbourne, adopted a typically Australian it-could-be-worse attitude. "You should be on the highlands of Bolivia at 5,000 metres," he said.

No, I shouldn't. I should be home in Melbourne. Mount Dandenong is plenty high enough for me.

In less than an hour we had climbed more than a thousand metres. From the top, the Mirador, we looked back to the town of Huehuetenango. You pronounce this Way-way-to-nango (rhymes with mango). I amused our hosts by suggesting most Australians would pronounce it Hewey-Hewey-to-nango.

Children in their colourful Indian clothes ran up as we got out of the cars and gave us yellow wild flowers. We gave them a few coins.

The view was spectacular beyond words. Many families live and work these steep slopes. They have virtually no money, but they do have million dollar views. Unfortunately, you can't eat a panorama.

The Business Of Empowering People To Transform Their Worlds

Over dinner the night before we had discussed our vision for ministry. Sitting around the table were Annette de Fortin, the World Vision field director, Javier and Hugo, two of her senior managers, Mario, the local area manager, Corinna Villacorta, a Peruvian colleague now working in Guatemala who had come along partly as my interpreter, Julio and Liszet, the local facilitators, and the visitors, Geoff and me.

I said we wanted to be in the business of empowering people to transform their worlds. (We had a bit of trouble translating empowering into Spanish, but between Geoff and the rest we worked it out to their satisfaction.) Empowering people meant doing the best development ministry we could. I said we wanted people in the field to say what was needed to transform the lives of the poor. Then let us think together about how we could create a relationship between the people in the project communities and our supporters.

At first I think our colleagues were sceptical that we really wanted them to have a blank sheet to work on. ‘Will your donors accept this?' asked Mario.

‘That's part of our challenge,' I replied, ‘we haven't found the donors yet. We are now making some undesignated funds available so you can get started. Then as we understand what you are doing better, we can begin to develop a strategy for communicating that to our supporters. I'd like you to help us in that too. And I'd like the community to know what we are doing in the support office.'

The hotel owner came over to tell us she wanted to close the restaurant. We went to bed. I heard later that everyone else sat up late discussing our suggestions.

Good Development Practices Are Hidden In Good Process

Next day we headed up the mountains. We talked as we bumped and slithered along the poor roads. Gradually trust began to emerge.

top of the mountain we came upon a high plain. At the end of the road was a small township, La Haciendita. When we arrived a dozen men surrounded the vehicles and welcomed us gladly. They knew Julio and Liszet.

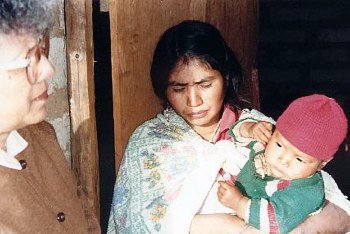

top of the mountain we came upon a high plain. At the end of the road was a small township, La Haciendita. When we arrived a dozen men surrounded the vehicles and welcomed us gladly. They knew Julio and Liszet. Annette, who was a medical doctor, discovered that the baby had a tumour of the umbilical cord. He needed to go to hospital, but the family had no money for the bus. A child might die for the lack of a bus fare, I realised. I asked whether we could help, and Geoff assured me it had already been taken care of during our conversation. Liszet was going to see to it.

Annette, who was a medical doctor, discovered that the baby had a tumour of the umbilical cord. He needed to go to hospital, but the family had no money for the bus. A child might die for the lack of a bus fare, I realised. I asked whether we could help, and Geoff assured me it had already been taken care of during our conversation. Liszet was going to see to it.