1978-87

My first encounters with the world, as the following stories from Korea, Kenya, Uganda and Somalia show, concentrated on my discovery of just how different the world was from home.

I discovered that there is such a thing as a ‘world view' -- a way of looking at the world.

Sometimes, as in Korea, I discovered that this world view is part of cultural difference. It touches matters such as how one negotiates and how one deals with conflict and criticism.

In Kenya I discovered that people have different priorities. They give value to things, events and experiences in ways that I found diferent and unexpected. Finding myself again in India, I discovered that words mean different things in diferent places.

My journey plumbed new depths of discovery in Uganda where I ran up against new and disturbing realities. By that I mean that what was considered the real world by Idi Amin and his government was quite different from how I experienced it. It seemed to me that they had constructed a world of macabre and unreal rules, values and beliefs. Yet it seemed not at all unreal to them. This was hard to understand.

In Somalia I found that I carried stereotypes in my head about Africa and Africans. Looking back, much of these recollections reveal my gaucheness and naive. In my diaries I find I concentrated on differences, treating these differences as bizarre and amusing.

In Somalia, too, I first began to flesh out the complex reality of the aid business I had joined. I had intellectual theories about it; now I discovered that the real world of aid was even more complex and chaotic.

Learning to Negotiate in Asia

Seoul, Korea in early 1978 was cold and bleak. It was not snowing, but snow piled up icily all around

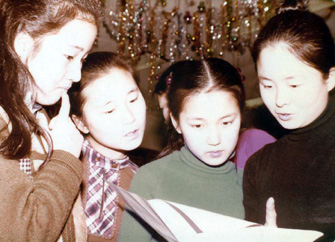

The World Vision Music Institute was near the airport and it was warm and welcoming. Mr Yoon was the choir conductor. Peter Lee, our director in Korea, explained that David Longe and I would meet with Mr Yoon to discuss the program for the visit to Australia of the Korean Children's Choir. But first, we were taken to the Music Institute for a welcome.

The children were waiting and said, in heavily accented English, ‘Good evening, Mr Longe. Good evening, Mr Hunt.'

I said, ‘G'day', and the children tittered.

We sat and the children sang a bracket of songs. What showmanship. What thoughtfulness. At first, something forgettable from a musical to warm us up. Next, a beautiful Korean folk song, mournful, gentle, soulful. Then, the stab in the heart, ‘Waltzing Matilda', sung slowly, a capella, in beautiful high harmonies. I wanted to go home: I wanted to stay here forever. Finally, ‘The Lord's Prayer'.

We sat and the children sang a bracket of songs. What showmanship. What thoughtfulness. At first, something forgettable from a musical to warm us up. Next, a beautiful Korean folk song, mournful, gentle, soulful. Then, the stab in the heart, ‘Waltzing Matilda', sung slowly, a capella, in beautiful high harmonies. I wanted to go home: I wanted to stay here forever. Finally, ‘The Lord's Prayer'.

It was impossible to say thanks properly. We had been drawn in, knocked down and possessed by the enchantment of this choir.

I heard them sing often after this, but to me they never sang as well.

Buoyed up, we prepared for our discussions next day with Mr Yoon. These took place at a new hotel high on a hill above Seoul. Peter was our interpreter and adviser.

David began by hoping that we might reach a wide audience for the upcoming Year of the Child tour. Peter translated. Mr Yoon responded in gentle tones and his body relaxed. Peter said, ‘Ah, Mr Yoon have same opinion.'

‘Perhaps we could discuss some of the classical repertoire?' suggested David. So we discussed and agreed to five or six numbers from the classics.

‘I was wondering if we might have some Australian folk songs', ventured David next.

Peter translated and Mr Yoon sat forward, his voice still gentle and agreeable.

Peter said, ‘Ah, Mr Yoon have different opinion.'

This seemed reasonable, but it soon became clear that Mr Yoon really only wanted to perform serious music. Perhaps one bracket of three folk songs, but the rest should be serious.

David and I saw people falling asleep in the stalls. Or worse, not turning up at all.

David tried. He suggested light classics. Then show tunes. Then pop songs. Each time Peter translated, and Mr Yoon became more agitated. His voice descended into a guttural growl. His head shook. And his right fist started pounding the arm of his chair.

Each time Peter would listen carefully, then turn towards us, a deep, calm pool of serenity, and say slowly, ‘Ah, Mr Yoon have different opinion'.

When David mentioned Abba, who were big at the time, Mr Yoon did not wait for the translation. He launched into a venomous tirade that needed no interpretation. Peter waited for this to subside, then said, ‘Ah, Mr Yoon have different opinion'.

I had visions of Mr Yoon throwing the lounge chair through the twelfth-storey window, and himself after it. And Peter, watching the body descend, would turn and say calmly, ‘Ah, Mr Yoon have different opinion'.

I learned from David and Peter my first lesson in Asian negotiation. Australians tend to go to the heart of the matter. Our tendency is to get the big issues out of the way first, then the little issues are swept away in good humour. This does not work in Asia. Indeed, it is usually thought to be very rude and barbaric. Civilised people, in Asian terms, skirt around the edges of difficulties. Deal with all the easy bits first. Gently probe the harder issues. Retreat often. Find small compromises. Little by little the problems are solved.

Neither approach is right nor wrong. They are simply different. And to complicate things further, I have also found some of the rudest and most direct people in Asia, and the most obtuse and gentle negotiators in Sydney.

Introduction to Africa

Soon after the Korean visit, I was on my way to Kenya. My companion was Ossie Emery, a Sydney film-maker and photographer very experienced in Third World travel. He was an ideal teacher for the new boy. Much of what I learned about how to behave, what to expect and how to cope, I learned in those first few trips with Ossie.

Ossie was also a marvellous but unstoppable raconteur. If interrupted in the middle of a story, he could pick it up again midsentence a day later.

African Weather Forecasts

In Kenya I saw the Mathare Valley and the Eastleigh community in Nairobi. We travelled into the countryside, including a visit to a Maasai community in the Rift Valley. These are all worthwhile stories in their own right, but I mention only two incidents.

The first happened one day while walking through a village. I looked up at the clouds and commented, ‘Looks like rain, eh?'

The farmer walking beside me looked up at the same clouds, appeared to analyse what he saw, and said, ‘Yes, it will rain at four o'clock'.

I was impressed with such forecasting. ‘At four o'clock, eh? How do you know?'

‘It rains every day at four o'clock.' He didn't need to look into the sky to know.

Dam Proof and Documents

Similar logic was applied by this farmer to World Vision's reporting requirements. Our office in Nairobi had been pressuring him for quarterly reports on the progress of a dam he was building and we were financing. He took us out of the village and showed us an impressive circle of earth containing many millions of litres of water. ‘I don't know why you people want a piece of paper that says I have built the dam', he said. ‘There's the dam.'

I couldn't argue with his logic. Seeing was believing.

“Damn Hard To Fly Without The Engine!”

The second incident occurred when we flew in a single-engined Cessna low under Lake Victoria clouds. It was a bumpy and uncomfortable ride, although there was little danger. Nevertheless, when we landed I put my hand on a propeller blade, took a firm hold, shook it and said, ‘Well done,' to the aeroplane.

The second incident occurred when we flew in a single-engined Cessna low under Lake Victoria clouds. It was a bumpy and uncomfortable ride, although there was little danger. Nevertheless, when we landed I put my hand on a propeller blade, took a firm hold, shook it and said, ‘Well done,' to the aeroplane.

To my surprise, the blade rattled under my grip. I had assumed it would be rock solid.

‘That blade is loose', I said to the pilot. ‘Is that right?'

The look of alarm on the pilot's face confirmed that it was most definitely not right. It was late in the day, so the pilot decided to leave the problem overnight.

Next morning, he called base in Nairobi and they asked him to check certain things. While he did this, another pilot came over. He was a white Kenyan with a colonial swagger, a thick moustache and an accent more British than British.

‘I say', he said, ‘trouble, what?'

‘The propeller is loose.

‘What-ho. Propeller loose, eh? Wouldn't fly in that one. Had a friend once with a propeller loose. Vibration so bad, engine fell out.' He paused for effect. ‘Damn hard to fly without the engine.'

We flew with him. Later a replacement propeller was flown up and fitted. The mechanic who repaired the plane flew back in the plane he had repaired. I was told this was a common practice that helped to keep mechanics' minds on the job.

To Bribe Or Not To Bribe?

On this trip I was also planning to retrace some of my Indian steps, to report on the progress made since the cyclone. But one small matter had been overlooked -- a yellow fever vaccination.

Fortunately I discovered the oversight when I arrived in Nairobi, and at the airport a doctor gave me the jab and stamped my yellow vaccination book. Now I only had one problem. According to the book, the vaccination took ten days to be effective. I was due to leave for India in seven days.

‘Don't worry', said the Kenyan doctor. ‘Everyone knows that this vaccination is effective in seven days. The extra three days are just a safety factor. If you don't have yellow fever in seven days, you are not going to get it.'

Thus, on the seventh day, Ossie and I flew into Bombay.

The man at the health counter inspected my book and said, ‘You do not have a valid yellow fever certificate'.

‘I know that', I said confidently, ‘but, as everyone knows, the yellow fever vaccination is effective after seven days'.

‘You want to see my book?' the man asked me. I didn't understand. ‘My book', he said, producing a book the size of a pulpit Bible, ‘says ten days'. Then he added, ‘Perhaps we can come to some understanding'.

Naive in matters of negotiation, I took my papers and went off to the side to discuss things with Ossie. ‘He wants you to offer him a bribe', he said.

‘Should I?'

‘Well, I wouldn't. But it's up to you.'

I felt distinctly uncomfortable about adding to the corruption of the Third World, so I decided not to offer him a bribe. And I have never offered, nor paid, a bribe since. It is possible, of course, that someone else has paid a bribe for me without telling me. I went back to the counter and asked the man what my options were.

‘You can take the next plane out. Or you can go to the Yellow Fever Quarantine Hospital for three days.' Naturally, he was not going to add, ‘or you can offer me a bribe'.

Ossie and I discussed these choices and decided to take the next plane out.

‘Unfortunately, there is no plane out until the morning. You will have to go to the Quarantine Hospital and make later arrangements.'

‘Is there a phone there?'

‘Oh yes, there is a phone there. You will be well looked after.'

‘Can my friend come and visit me there?'

‘Of course. He can come and go as he pleases.'

In Jail In Bombay

I joined a young Indian man in a van and we disappeared into the night. His story was a misery. Studying in Kenya, he had ten days leave to visit his family on the other side of India. He would spend the entire time in the Quarantine Hospital.

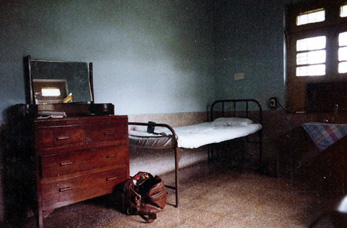

It was not a hospital but a jail.

The windows and doors were barred, although one could move about inside quite freely. Purpose-built many years before, it had individual rooms, each containing a wooden bed, a chest of drawers and a chair. Shuttered, windows without glass opened onto an overgrown garden, visible through the bars.

The windows and doors were barred, although one could move about inside quite freely. Purpose-built many years before, it had individual rooms, each containing a wooden bed, a chest of drawers and a chair. Shuttered, windows without glass opened onto an overgrown garden, visible through the bars.

Lonely and disorientated, I fell into bed, resolving to call Ossie the next day and get on our way.

Meanwhile Ossie found his way to our hotel. Next morning he tried to get things moving. He rang the phone number he had been given for the Quarantine Hospital. It rang and rang. No-one answered.

Back at the hospital I had discovered that, yes, there was a phone there, but, no, it was not working.

Another Lesson in Indian Communications

Undaunted, Ossie asked the information desk where the Quarantine Hospital was. Nobody knew. He called the Department of Health, the airport authorities and anyone else he could think of Only the airport authorities showed any recognition.

‘Yes. The Quarantine Hospital. What do you want to know?'

‘Well, I have this number, but it just keeps ringing.'

‘I'll get the number for you.'

‘OK.'

The man gave Ossie the number he already had.

‘Yes, but no-one is answering at that number.'

‘Oh yes, sir. The phone is not working.'

I Am Found!

Outside on the taxi rank, Ossie finally found a taxi driver who claimed to know where the hospital was. Ossie said that he would hire him for the entire day if he first would take him there.

About mid-afternoon Ossie turned up. I told him about the snake on the floor of the bathroom. I told him about the curry I had tasted at lunch. I told him about my decision to go on a hunger strike until he got me out. He told me that the phone didn't work.

‘Oh, really?'

He agreed to get me a typewriter so I could work while he tried to get me out. He accomplished this by asking for a typewriter to be put in his room back in the hotel. In 1977 ordinary typewriters were not very portable. This one was a metal-framed Olympia. Ossie put it under his arm and marched out through the lobby.

I stayed in the hospital for three days. It took so long to move the bureaucracy that, in the end, a flight out became available at the time I was due to be released anyway.

The President with Blue Hair

Two other journeys during this period are especially relevant in my journeys towards justice: Uganda and Somalia.

The international president of World Vision was Dr Stan Mooneyham. Stan was a charismatic figure, tall, articulate, good-looking. He was also an American who carried his culture with unconscious comfort. When I started with World Vision, he had recently put a blue rinse in his greying hair. This may have been kosher in California, but it was strange in Sydney, and eccentric in Ethiopia.

Nevertheless, just as you cannot judge books by covers, so neither can you assess people by the colour of their hair. Stan was a beautiful man, a gifted communicator, even if, at least then, flawed by an apparent belief in his own image. I did not know him well, so what I report can only be my impressions.

I travelled with him a few times, once in Australia, once in Uganda and once in China, his last official business for World Vision at the end of his presidency in 1982.

Idi Amin and My First Taste of Banana Pizza

In Uganda, in May 1979, Idi Amin was on the run, The Tanzanians had ‘liberated' Uganda from Amin's oppression (only, as time would reveal, to subject it to a greater oppression). World Vision had been poised on the border to follow in Amin's wake with relief supplies to the victims of the fighting. As Amin left Kampala our trucks crossed the border.

Two days later I was in Kampala with TV presenter Anne Deveson. We joined a team led by David Toycen, then World Vision's international communications director, who was making a documentary for American television starring Stan. We were among the first arrivals in many months, and the Kampala airport was total chaos.

We found rooms at the Inter-Continental. It sounded grand, and it might have been, but now little in the hotel was working. The chef, however, was an artist: supplied only with bananas in quantity he managed to provide a different menu every day. Pizza base made with banana rather than flour was, I thought, a significant culinary achievement.

American Journalistic Gauche

There were many memorable moments on this visit. One involved a young American woman who inveigled herself into our convoy. She was the archetypal gauche reporter. She made Norman Gunston seem aware.

A Ugandan woman, daughter of a murdered judge, was describing the horror of the murder. The reporter took notes and kept asking breathlessly, ‘And then what happened?'

‘They took him outside.'

‘And then what happened?'

‘They took a machete and chopped off his arms.

‘Yes, yes. And then what happened?'

‘They chopped his head off.'

‘Yes, yes. And then what happened?'

‘Well, he died, obviously.'

‘Oh, yes. I see ... And then what happened?'

We thought it divine justice when her passport was stolen with her purse. Later her purse was retrieved from a pit latrine, but her passport was gone. To our shame, when we arrived back at Wilson airport in Kenya, we all deserted her at immigration while she was trying to explain how her passport was lost in a toilet. The last words I heard were from the immigration official: ‘Yes. And then what happened?'

My First Taste of Institutional Murder

Such macabre lighter moments were necessary to balance the horror of Uganda at the time. It was my first encounter with systematic, paranoid violence. I had not seen Yad Veshem then. I had not seen the extermination camps of the Nazis. I had not visited the killing fields in Cambodia, nor the sites where Aboriginal people in my own country were slaughtered to. make way for the conquerors. This was my first encounter with a killing place.

It was called ‘The State Research Centre'. Its innocent face, a U-shaped three-storey office block, obscured a horrid interior.

Two days before, Amin's troops had made a fast exit. Within hours, Tanzanian troops liberated hundreds of people imprisoned inside. The foyer was a jumble of broken furniture and scattered books. A pile of smashed glass and pamphlets advertising sophisticated weapons lay against one wall. In the middle of this pile was a shattered portrait of Idi Amin, defaced by the inmates in futile but brutal revenge.

A priest from the Church of Uganda (Anglican) had come to show us around. He was one of the hundreds who had been liberated from the Centre. For thirty days he had been kept with up to thirty other men in a single cell about three metres square. It had a boarded up window and a door that was permanently locked. The guards did not attempt to care for their prisoners. Occasionally, a bucket of water would be provided, but sometimes days would pass and the men would start drinking their urine in desperation.

There was no toilet, so the men lived with their own waste.

There were many similar rooms for both women and men. The priest did not know how many people were there altogether.

Most people in his room had died, either starved or dehydrated. Twice during the thirty days of the priest's incarceration, soldiers came and took away the dead bodies. Meanwhile, the living piled the dead on one side and lived with the stench.

Quite regularly, two or three times a day, sometimes more often, soldiers came and took someone away. ‘We didn't know why some were chosen and some were not', said the priest. ‘Actually, we wanted to believe it meant that there was hope, that they were setting us free. But we knew deep down it was just another way to die. Still, it would have been a blessed release from this living hell.'

He took us to a door off the foyer. As he opened it, a sickly, musty smell came from the room below. We went down. It was dark, and I put my hand out to balance myself against the wall. The wall was sticky.

The priest turned on a light. We were standing in an abattoir. The walls and floor were caked with dried blood. A large wooden block in the centre of the room was the only furniture. The priest put his neck on the line, to show where the prisoners had been brought for their execution.

It was a place of unspeakable evil and horror. For many years I pushed the memory of it away.

But how did people come to be in this place? Were they convicted of crimes? Were they spies? Saboteurs? Political activists?

Hardly. Whatever the original motivation, the ultimate reality was that Idi Amin was systematically killing off all supposed opposition. The priest's own case showed the lunacy of Amin's last days.

One night the priest drove his car to a suburban hotel for a meeting with some members of his congregation. In the car park he found a parking place beside a grey Mercedes-Benz. He should have been alert to the fact that this car was parked with spaces either side of it, but nothing registered.

It was Idi Amin' s car. Such was the paranoia that anyone who parked their car next to Amin's was suspected of treachery.

Later that evening, the priest was woken from sleep. His internment began immediately. Nobody knew where he had gone until he turned up at home thirty days later.

Africa is More Multicultural then I Expected

Ahuma Adodoadji, from Ghana, accompanied us into Somalia. His companionship unwittingly revealed a stereotype in my thinking. Often I hear people talk about Africa as if it is monolithic. They say ‘Australia, France and Africa', as if Africa were a single country. It is, of course, enormously varied, politically, geographically, culturally, musically. I too was guilty of accepting this stereotype. I assumed, because Ahuma was an African, that he would be at home in Somalia. I found that he was even more out of place there than I was.

We discovered this on arrival at Mogadishu. I was travelling with Ossie Emery, Anne Deveson and Stuart Mudge (our sound recordist). We were to make a documentary about the refugees who were crossing the border in northern Somalia to escape fighting between Ethiopia and Somalia. Called On the Margin of Life, it was to be highly commended in the United Nations Media Peace Prizes that year.

One problem about the arrival of aid workers is that it distorts local prices. Sometimes aid workers are a little too quick to pay the asking price because it seems so cheap by international standards. We miss the fact that the price being asked is ten or twenty times normal. Worse, if we say ‘yes', we set the price for the next person.

This must have happened with the taxi drivers in Mogadishu. A few days before, some United Nations people had come through. When I asked a taxi driver for the price to drive us from the airport to the hotel (about two miles) he said, ‘Fifty dollars'.

To be honest, I didn't believe my ears. I don't mean metaphorically; I mean I literally thought my ears were not working. He could not have really said ‘Fifty dollars'. But he had.

‘Ahuma, this is outrageous', I said ‘Can you negotiate with this fellow?'

It soon became clear that Ahuma could not. An able man who later directed an entire field operation for World Vision, Ahuma was out of his depth with Arab-style trading required in Mogadishu.

I weighed back in and negotiated a nine dollar fee. Even that must have been thirty times the real fare, but there was a matter of face involved for the driver, having started so high.

Fine Dining - Mogadishu-style

Our hotel in Mogadishu was built around a courtyard with a lovely poinciana tree spreading shade over an al fresco restaurant. It was old and run down.  Built in the grand Italian colonial style, it was a modest, tranquil haven. The hotel was destroyed, along with much of Mogadishu, a decade later.

Built in the grand Italian colonial style, it was a modest, tranquil haven. The hotel was destroyed, along with much of Mogadishu, a decade later.

Built in the grand Italian colonial style, it was a modest, tranquil haven. The hotel was destroyed, along with much of Mogadishu, a decade later.

Built in the grand Italian colonial style, it was a modest, tranquil haven. The hotel was destroyed, along with much of Mogadishu, a decade later.

So too, I suppose, was the rooftop restaurant we ate in one cloudless evening. We climbed stairs on which it was easy to .confuse the banister with the loom of electric wires that connected everyone in the building to the electricity grid. A few old tables were scattered about upstairs. The restaurant lacked all pretension, but it possessed style and a good range of splendid pasta.

‘Would you like wine?' asked the waiter.

‘Yes', I said, ‘bring the wine list.'

The waiter looked at me strangely and walked away. Moments later he returned with a bottle of red wine in each hand. ‘There is claret and rose', he said, showing his left and right hands. This was the complete list.

Instant Cities in the Desert

In Hargeisa, in the north, World Vision had rented two houses as a base. Our medical team was one day ahead of us. When we arnved, they were preparing to visit the refugee camp to survey, so we joined them.

About an hour's drive away along sandy tracks, the camp had only one feature that commended it as a place to live: a river. A dry river, but water was available a metre below the surface. Otherwise, it was a barren place. Already 10,000 people were living there in huts made from branches and plastic sheets. No trees were visible for a kilometre circle. As more people came, the daily walk for firewood would push this circle out another five kilometres.

There was little food and it was being distributed without experienced or effective organisation. Our medical team, led by Sri Chandar from Singapore, knew what to do and set about it quickly. A feeding centre was set up for the children and assessments were rapidly made of the worst cases. A secure area was created for storing supplies. A medical centre was set up and began treating people. As supplies were needed, they were unpacked and put on shelves. Organising, by doing.

By the end of the first day, a minor miracle had been accomplished. But more needed to be done.

The Somalian army was trucking in people by the hundreds every day. Nomadic people, ethnic Somalis like the locals, they roamed in nearby Ethiopia, across a border drawn without regard to their ethnicity. When the war came, they were caught in the cross—fire. Their water holes were seen as strategic so the water was poisoned. When their cattle and goats died, the people followed a time-honoured response. They folded up their homes and walked.

When they hit the Somali border, they were picked up and brought here.

The trucks would stop, disgorging the people from the back. Confused and shocked, with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and sometimes a cooking pot or two, they would immediately begin to make a home. Their industry was amazing.

For many, rescue into this alternate misery came too late. Many children had diarrhoea, and within a few hours they were so dehydrated, they died. Weaker ones, older men and others, also died.

Relief Now, But What Next?

Into this hell I saw World Vision bring hope. We brought stability where there had been confusion and progress where there had been decay.

But all around other issues conspired against us and the people. The war was the biggest. Until it was solved every step forward was merely coping.

I realised there in northern Somalia that our work existed in a context which needed to be taken seriously. This was not a new insight. Many others had discovered it before me, and indeed, I had given it intellectual assent long before I had ever heard of World Vision. But here I experienced the practical implications of the idea. These people needed help right now. That was certain. But there was a sense of futility about that help while the war waged around us unabated.

Some people, usually far removed from the pain of refugee existence, argue that ‘the real problems' have to be dealt with. By ‘real problems', of course, they mean the underlying causes. They are right to say these must be dealt with; peace is a prerequisite for effective development. But they are wrong to imply that these are the only ‘real problems'.

Nothing is so real as the death of a child. It blights a parent s life more deeply than anything so generalised as war, famine or epidemic.

There is no deeper, more painful sound than the sound of a mother who wakes in the morning to find one of her children has died in the night. Every morning in the refugee camp began that way. Holistic thinking, the thinking of God's kingdom, requires us to meet people where they are and to react to their context as well as their need. It is not a matter of either/or.