The Smell of Human Air

The Chinese have a name for it. Yahn-hey. Human Air.

The aroma of people is the most enduring memory of that first time I arrived in Bombay. It would be unkind, and wrong, to call it a smell. Although you could certainly smell it. But the odour was not the coarse, acrid unpleasantness of body odour. It was the sweet, fetid, warm, thick smell of people. Many people. Very many people.

Bombay was my first overseas experience. A perfect beginning. In the thirty years of my life before that day I would always respond with a wise crack if asked about overseas travel.

"Been overseas?"

"Sure." Said matter-of-fact. Be cool.

"Oh, really? Where?"

"Bribie." Said without emphasis. Best to be droll if you cannot be genuinely cool. Bribie Island is a large sand hill off the coast of Queensland, an hour's drive north from Brisbane. It is separated from the mainland by a passage across which most young Australians could swim.

The first whiff of Bombay touched my nose as the plane's air conditioning took its first gulp of local air. Like Hong Kong, where one's arrival by air was marked by the sucked-in smell of an open sewer. Bombay too, had its own arrival smell.

But it was at the top of the stairs leading down to the rattly bus that the aroma struck me. The hot, humid night air seemed to combine with the perspiration of ten million people. It was redolent of sweat, incense, and human endeavour. The very air seemed full of life. Within minutes, I understood where all this lively air came from. It came out of the people. I could feel the hot air sucking the energy right out of me.

We are all innocents abroad when we make our first overseas trip. I was attempting to obscure my fear under a veneer of inscrutable confidence. I had already discovered that the less one says the more confident one appears. There's nothing less confidence inspiring, for example, than a driver who draws everyone's attention to all the road dangers the driver is observing. Observe, but let the rest of them decide for themselves what they want to worry about.

A Brand New Passport

It was 30 November 1977. A few days before I did not have a passport. Now I had K855340 in my pocket with twenty-four blank pages and one Indian Visa.

A week before, a cyclone and tidal wave had swamped part of the east coast of India. World Vision of India had decided to help the victims. As part of the international network of World Vision organisations, World Vision Australia, for which I worked, needed to raise money for the relief effort.

We waited vainly for the story to be picked up by the Australian media. It rated merely a few paragraphs in the World News pages of the serious newspapers. Nothing elsewhere. Television images were not available quite so easily then. So Australian television news did not mention the fact that perhaps 20,000 had died in one night as a tidal wave swept in from the ocean. A few radio stations picked up the story, but it rated no mention after the longer 7:45 am bulletin on the ABC. If World Vision were to raise any money to help, we would need the story to be better told.

Persuading Mike Willesee

I rang Mike Willesee. He was fronting Willesee at Seven on the Seven network, against A Current Affair on the Nine network, hosted by Michael Shildberger. We did not know if Willesee knew about the disaster, or even if he knew about World Vision. In those days, we were not quite the household word, that we became later. I had never spoken to Willesee before. I didn't even know if he would take my call.

"Trans Media, Good Morning."

"Could I speak to Mike Willesee please?"

"Who's calling, please?"

"Philip Hunt from World Vision."

"Hold the line please." To my surprise the next voice I heard was Mike Willesee's. He was very friendly.

"Hello, Philip. What I can I do for you?"

I explained about the cyclone and tidal wave in India. Yes, he had heard about it.

"I have to say, Philip, it's not our usual story."

"I realise that. No-one else on TV has given it a mention." I added, "And we could help with the airfares."

"Well, that would certainly make the story more accessible for us," replied Willesee, "but I can't see how it's an economic proposition for you people."

"Last year when 'Four Corners' ran our documentary on Ethiopia . . . "

"The one Anne Deveson did? I remember it."

"That's the one. It showed one night. We raised a million dollars."

"Phew," whistled Willesee. The power of television is in its reach. We knew that if we could get a few million Australians to see what was happening in India, we could follow up with advertising and direct mail. We could raise some of the money that would be needed.

"Leave it with me," he said and hung up.

An hour or so later, Phil Davis, Willesee's executive producer called back.

"I don't want to do this story," Davis said up front, "but you've managed to convince Mike. He's very excited about it. That's good enough for me."

Off To India

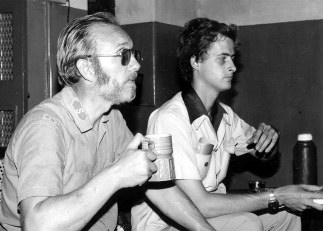

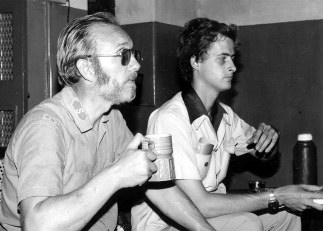

Within a couple of days I found myself on my first overseas trip, and on my first trip as coordinator for a film team. A young Howard Gipps was the reporter. John Bowring, the cameraman. I heard later he made a killing by investing in Paul Hogan's "Crocodile Dundee." And a sound technician, Ian, whose long hair was, and still is, de rigueur for sound techies.

India was still then a tricky place for film crews to visit. There was a risk that we would not be permitted to bring our equipment in at all. There was a risk that we would not be permitted to film where we needed to. There was a risk that we would not be allowed to bring out the film we shot, or, at least, be required to submit it for local processing and inspection. Any of these risks would scuttle a current affairs story. Our plan was to be in and out in four days.

Four days was about the fastest one could cover such a story in the late '70s. Fifteen years on you could do it all on videotape, edit on location, and transmit the result via satellite. You could shoot in Africa today, and have the story in the local newsroom tonight.

In 1977 few were using video. The technology was bulkier than film. And although video was as reliable as film, it was always theoretically possible to repair a film camera if it broke down. When a video camera broke, it usually needed a replacement part. Sony doesn't have spare parts in Lalibella, Ethiopia, or Hargeisa, Somalia, or Vijayawada, India.

The Man On The Bus

I was a worried man. Although I was sure I looked calm enough.

"You are Mr Hunt?"

The voice came from an Indian man on the bus that was to take us from the plane to the terminal.

"Mr Sojwal rang me and asked me to help you through customs and immigration." Sojwal was our India director.

I shook his hand with unintentional vigour. As I look back I can see how remarkable his presence was. It is rare, anywhere in the world, for fixers and helpers to be allowed into the secure airport area. More rare in those places where there is paranoia about film crews. Of the many countries I have visited this experience of being welcomed before the immigration counter has only happened in a few places. China, Lebanon, Cambodia. And India. In Lebanon, Jean Bouchebl, our local director, arranged for a huge Chevrolet to pick me up at the foot of the gangway. Totally unnecessary embarrassment, but what a buzz!

I don't know whether my Willesee at Seven colleagues were impressed by this level of organisation. I suspect, like me, they thought this was simply World Vision doing its usual professional, well-organised best.

The next half an hour was a blur of heat, aroma, confusion, and the constant, noisy press of people. John produced his long list of equipment. It was inspected and stamped under the watchful eye of our fixer, a man who worked for the Bible Society in Bombay. Our fixer organised three tiny taxis and argued angrily with the three hundred boys who laid hands on each piece of luggage, each claiming a right to porterage. I was thankful for his local knowledge, else our total budget might have disappeared into the hands of Bombay porters.

Soon we were in a nearby hotel with the chance to catch a few hours' sleep before the morning.

Buying Rupees

The fixer arrived at nine to take me to a Bombay bank. A friend who had left India a year or two before had left some money behind in this bank.

"You should use it while you are there," he had advised, "I cannot bring it out. So you may as well use it."

With justified but naive faith I allowed the fixer to handle all the arrangements. Although there was no particular difficulty, it nevertheless took almost two hours to withdraw and count out a few tens of thousands of rupees.

Meanwhile, back at the hotel, the camera crew were already at work shooting local colour including the obligatory snake charmer in the hotel forecourt. There was no opportunity to see the rushes, and these shots never ended up in the report.

Meanwhile, back at the hotel, the camera crew were already at work shooting local colour including the obligatory snake charmer in the hotel forecourt. There was no opportunity to see the rushes, and these shots never ended up in the report.

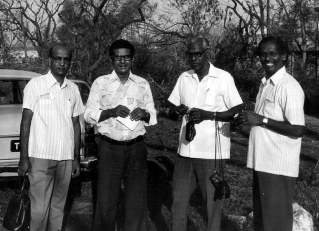

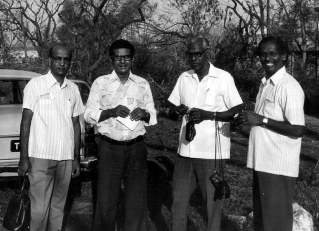

Our fixer got us back to the airport for a domestic flight to Madras, where World Vision's main office was In Madras we were met and welcomed by Bhaskar Sojwal and some of his senior staff and taken to a hotel.

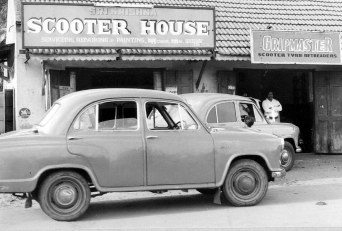

The Phenomenon Of Indian Cars

I was amazed by the cars. Motor cars have always had a fascination for me. Before I was 12 I could name every make and model of every car on the roads. I would sit on the front verandah of our home in Church Street, Parramatta and recite the names of cars as they sped by in four lanes.

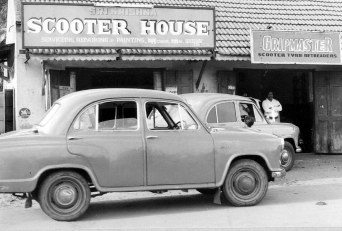

In India it was like a journey back to the '50s. The cars had different names, but they were Morris Minors and Austin Cambridges. I suppose some State run industry had bought the moulds from Austin-Morris and were stamping out these venerable machines in a market protected from imports. We were to discover that these vehicles had inherited all the unreliability of their forebears.

In India it was like a journey back to the '50s. The cars had different names, but they were Morris Minors and Austin Cambridges. I suppose some State run industry had bought the moulds from Austin-Morris and were stamping out these venerable machines in a market protected from imports. We were to discover that these vehicles had inherited all the unreliability of their forebears.

The other traffic phenomenon that one became aware of was that the horn is an essential element of normal driving in India.

"If you have an accident," said our driver seriously, as if explaining something logical to a small boy, "and you haven't sounded your horn, you are in the wrong."

There is a branch of sociology called ethno methodology. In it, sociologists describe the taken-for-granted rules of a society. Traffic is one place to see that these taken-for-granted rules exist and vary from place to place.

In Australia, when there is a traffic jam, people stay in their assigned lanes. In most parts of Asia, the road markings become incidental in such circumstances. People just crowd their cars into any available space. A two-lane road can hold six cars abreast if you try hard enough.

One Indian traffic ethno methodology is to drive right up to a problem, then wait for someone to reverse out. In Australia, drivers will hang back and leave some space if there is no obvious way forward, or if someone in front obviously needs to move first.

And, in India, of course, you blow your horn always.

We horned off to the office in a brand new, 1978 model, 1962 Austin Cambridge. World Vision was housed in a couple of buildings that, like most buildings in India, seemed to me to have seen better days.

Confronted By All The Differences

Why don't they paint them? I found myself wondering. What I hadn't worked out at this stage was that an Indian visiting my country might be wondering why we did paint our houses.

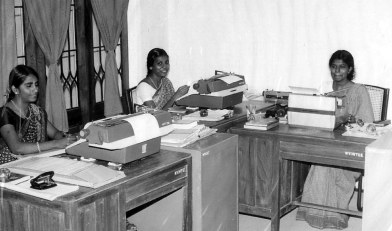

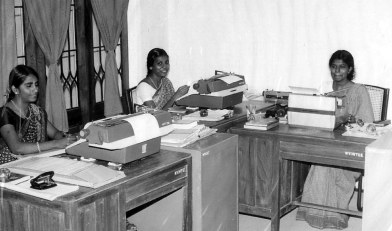

Inside, young ladies in saris were crowded together in hot rooms. I thought it was intolerable. These people need more space. I was thinking. They need air-conditioning. They need a Coke machine.

Inside, young ladies in saris were crowded together in hot rooms. I thought it was intolerable. These people need more space. I was thinking. They need air-conditioning. They need a Coke machine.

Some years later, while living and working in Hong Kong, I generously arranged for each of my staff members to have a desk of their own. To my surprise I soon found desks left vacant while two people sat together at another desk, and two desks pushed together where before each had a private space.

"We work better this way," my Chinese staff taught me.

Sojwal gave us tea in his office and we discussed our plan. We would fit into two cars. The brand new Austin Cambridge and another older car that looked more than a bit like an Austin A40. We would drive to Vijayawada, a port city of the State of Andhra Pradesh, north of the area devastated by the cyclone and tidal wave. It was over 200 miles, but if we left early in the morning, we could make it in a day.

The alternative, by train, had become impossible until repairs were done to the train line. And, anyway, we could use the cars when we were up there.

Before light we set off from Madras. As the first flickers of morning sun made red the sky I noticed that we were passing a long line of squatting men attending to their early morning call of nature. Somehow, (I can't believe I actually asked) I discovered that the women went into the fields. I made a mental note to be careful where I walked.

The English Make The Hottest Curry

We stopped for lunch at a hospital run by an English missionary couple named Scott. Assuming they would serve up fish and chips, I was rather unprepared for my first taste of serious Indian curry. I could not eat even the first mouthful. It seemed my whole face had been hit with buckshot. My nose went numb, and all my teeth seemed to have separated from the jaw. Taking pity on my distress, they offered a banana, the perfect cure for curry. I remember thinking that it must have been a practical joke. No-one ate this for real, did they?!

We stopped for lunch at a hospital run by an English missionary couple named Scott. Assuming they would serve up fish and chips, I was rather unprepared for my first taste of serious Indian curry. I could not eat even the first mouthful. It seemed my whole face had been hit with buckshot. My nose went numb, and all my teeth seemed to have separated from the jaw. Taking pity on my distress, they offered a banana, the perfect cure for curry. I remember thinking that it must have been a practical joke. No-one ate this for real, did they?!

These days, I finally acquired a taste for curry, and can eat most hot dishes with enjoyment. It's amazing what the human body can become accustomed to.

When The Car Breaks Down...

Into the afternoon, the A40 expired. We sat in the hot sun for half an hour while people wagged their heads and muttered together. The Indians were enjoying the discussion. It was a chance to add spice to their relationships. If they could talk about this for half an hour it would be a nice experience. For the visitors, talking about a problem did not rate as highly in our value system as actually fixing the problem. That doesn't mean we were right, of course. It just felt right for us to get the thing fixed.

So John climbed under the A40 and worked out what the problem was. Something to do with the diff, which he helped to repair. I guess, if you can fix a Bolex film camera, a motor car's differential seems pretty simple.

So John climbed under the A40 and worked out what the problem was. Something to do with the diff, which he helped to repair. I guess, if you can fix a Bolex film camera, a motor car's differential seems pretty simple.

A Liquid Enema

It was well into the night as we arrived near Vijayawada. We were accommodated on camp beds in a house next to a clinic. Whole families were living on the verandahs and in the run down garden, refugees from villages destroyed by the tidal wave.

Thirsty from the long, hot day, I took a sip of water from a large pot provided for washing. It seemed to me that the water went straight through me. No sooner had I swallowed than it came out the other end. That night I endured the first experience of Montezuma's Revenge, although I had always thought this to be a Latin American affliction. Over the next few years I discovered Montezuma has visited many countries. Even Europe and North America.

The necessary pills paralysed my bowels, and I prepared for the next day by screwing up the muscles of my sphincter so tight that my thighs ached. It took me a few years, and a few more bad experiences, but eventually I adopted the time-honoured practice of never drinking the local water anywhere. And never eating uncooked food, or fruit I had not peeled myself. Sometimes, the generous hospitality of hosts makes such precautions impossible. Then prayer has been a reliable option.

Blasted By The Cyclone

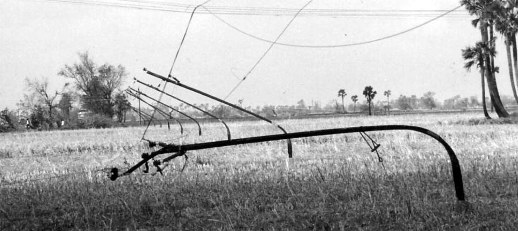

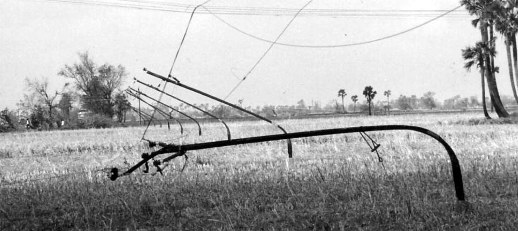

The devastation caused by the cyclone and tidal wave was immense. Huge trees were lying on their sides all over the place. The leaves completely torn off by the winds. Some landscapes looked bomb-blasted. Power poles were bent over near the ground, like Muslims at prayer.

Most people had simple houses. They were blown away. But if that had been all that had happened, we would not have been here. Cyclones are regular visitors to this part of India. Normally the people literally pick up the pieces of their houses, and rebuild.

Swept Away By The Tidal Wave

But this time, a wave of water hit the coast with such power that most of the villages on the coast in a strip 50 kilometres long were obliterated. Thousands of people were drowned instantly. The wave inundated villages five to ten kilometres inland.

Fire, Aim, Ready

This much we knew as we set out for our first proper day of reporting. Before we had gone a few kilometres, Howard asked for the convoy to stop.

"I need that field" he said pointing to a field of half-grown maize. The heads of many stalks were stripped and damaged. The field was waterlogged with salt water and the remaining crop would certainly die soon.

Howard, John and Ian set up quickly in the field, and Howard did a walk through the field.

"I'm standing here in Andhra Pradesh," he said into the camera lens. Then he spoke authoritatively about the situation. I was surprised to hear this, because we hadn't seen the situation.

I realised that Howard already had the story written in his head before we arrived. He knew what to say. He knew what shots he needed. He didn't need to come here to find out the facts. He only needed to come here to get the pictures and the quotes and the stand-ups to make his story.

I saw the strengths and the dangers of current affairs television. It is not about reporting. It is not about going to get the facts. These are luxuries not available under the time constraints of current affairs. The reporter has to make quick assessments and judgements. They need to understand the story quickly. Then the task is to get the pictures.

A good reporter, of course, will get it mostly right, as Howard did then. But the danger remains that if a reporter begins with wrong assumptions, the product can be a grave and dishonest distortion of the truth. Yet it will appear true on television. Television can be a very credible medium. Even when it is telling us lies.

Death, Destruction and Joy

The stories were heart-breaking, and what we expected. People who had lost the rest of their families. A woman who lost her husband and children. Another who saved her baby by clinging to him in a tree as the waters rushed around them, only to discover that somehow he had drowned in her arms. A man sitting stunned and silent under a canopy of leaves. He said nothing.

But there were stories of joy too. People reunited after the night of terror. The one saved, when all others were lost.

In one place the whole village had rushed into a stone church building for shelter. Over a hundred people were crowded in when the wind pushed the walls over. A man and a young girl were the only ones to survive. They happened to be standing by the door as the building fell, Max Sennet-like, around them. All the others were crushed to death. When the winds died, these two pushed the door up and found their families quiet and still under the rubble.

In one place the whole village had rushed into a stone church building for shelter. Over a hundred people were crowded in when the wind pushed the walls over. A man and a young girl were the only ones to survive. They happened to be standing by the door as the building fell, Max Sennet-like, around them. All the others were crushed to death. When the winds died, these two pushed the door up and found their families quiet and still under the rubble.

Keep A Professional Distance

I found the whole experience quite meaningless. I could not take it in. And I didn't.

Without giving it much thought at the time, I found myself in something that was so beyond my experience that it had no meaning. It sounds trite, but it was like living in a disaster movie.

The cultural difference and the remoteness of a cyclone experience from my own world, served to keep the whole experience at a distance from my emotions. I reported it. I wrote things down. I took many photographs. I took the whole thing in, but not so far that it touched my heart, or my soul.

The wailing of one woman came spearing in towards my heart, but I managed to deflect the potential pain by suggesting we capture her story on film. When in emotional danger, become technical.

Within two days the story was in the can (in those days this was a literal statement as one of our suitcases was crammed with cans of Kodak).

Eating With Lepers

At this stage, Sojwal and the other senior people left us in the hands of George, a junior colleague. They went to host the international President of World Vision, Dr Stan Mooneyham, who was arriving by helicopter.

George took us to a leper colony for tea.

I knew about leprosy which, given its bad reputation is trying to rehabilitate itself under a new name, Hansen's disease. I knew it was not very contagious and that it was quite safe to visit with lepers. Naturally, as everywhere else in India, our arrival was a matter of curiosity. Crowds quickly gathered simply to quietly stare wherever we went. At the leper colony, there was rather more enthusiasm as we seemed happy to shake people's hands.

I admit to thinking about the danger that some of these hands might drop off mid-shake, but, of course, this was humour built on prejudice. It didn't happen.

"The people are very impressed that you show no fear" said the English Salvation Army officer who was the administrator here.

"I understand that leprosy is not as contagious as people used to think."

"That's true. But most people around here don't know it, or don't believe it yet. So the people here feel very affirmed by your openness towards them."

Inside, our hosts treated us to the first familiar meal of the visit. English-style roast chicken and vegetables. Our dinner was interrupted by a small bat which came searching for the light and did tight circuits of the dining room until knocked down with a broom.

First Attempt To Catch A Train

The plan was to go to Bapatla station and wait for the train the Hyderabad-Madras express. We had tickets and reserved seats. Just to make sure, George had left before dinner to catch the train up the line. He would meet us on the train.

At around nine o'clock we piled into a series of pedicabs, a kind of bicycle rickshaw, and formed ourselves into a pile of luggage and bodies on the station platform.

Time passed.

Time passed.

Our host family comprised the Salvation Army missionary couple, their bored, doe-eyed fifteen year old daughter who was visiting from England, and two adopted Indian boys. They waited a polite time, then begged their leave owing to the late hour. They reassured us that the trains were inevitably late owing to the cyclone, but that we only had to wait and the train would come.

We passed the time playing cards on a suitcase lid, and the crew shot some promotional pieces for Channel 7. Groups of people making 7-finger signs to the camera.

Soon after midnight the train arrived. I made myself responsible for finding George. I expected to see him hanging from a window, calling "Here it is" so I walked along the carriages searching for a familiar face. The others trailed behind with a few score of porters each carrying a kilogram of baggage. The train was crammed to the gunwales with people. Hundreds of faces peered out into the light of the platform, but none was familiar to me.

Before I was half way along, the train pulled out. And we were left on the platform, dumbstruck in surprise.

We were lost in India. Somewhere called Bapatla. Tomorrow we were scheduled to leave Madras for Singapore and home.

Try A Taxi From The Middle Of Nowhere

"Let's get a taxi," suggested Howard, full of enthusiasm. Howard was used to making things happen. He was a current affairs journalist for whom time did not wait.

"OK," I said without betraying my doubts and turned to one of the many locals standing around, staring. "Where do we get a taxi to Madras?"

The locals were dumbfounded. It wasn't just that my accent was funny. Or that people here were struggling with English as a second language.

The problem was that what I had asked was quite beyond their frame of reference. A taxi to Madras?!? That's two hundred miles. No-one takes a taxi that far.

Finally, we managed to get a couple of pedicab wallahs to humour us sufficiently to take us to wake up the local taxi-driver. There was only one. Howard and I sped off in separate pedicabs into the dark of Bapatla. As we left the light of the railway station and entered the quiet darkness of the little sleeping town, I felt vulnerable. I wondered how wise it was to be placing our lives in the hands of these people. If we went missing now, who would know where to look?

The taxi driver was not in a good humour and asked Howard for an amount of money that, in his terms, was exorbitant. Naively, it seemed to us a fair price. But a moment's consideration of the state of repair of the taxi convinced us that we would be better to wait for the next train. There seemed to us a high chance that we would find ourselves repairing more than the differential of this vehicle, and a moderate chance that we might fall among thieves en route.

"Let's go back to the leper colony, and ask for their help," I suggested. I refrained from adding Perhaps they can give us a hand.

Please Give Us Your Bed

Sometime around two in the morning, we all arrived at the front door of the darkened house of the leper colony administrator and his family. He came to the door in response to our knocking and, not having much choice in the matter, invited us in.

The daughter appeared in her pyjamas as if living out a dream-come-true. The day before she had latched onto Ian with his rock-star looks. Now some angel had sent him back to her. Ian just smiled with shy embarrassment.

"You can sleep in my bed," she volunteered. Her father gave her a withering look and she added, "I'll sleep out here on the lounge."

I'm ashamed to recall the way we forced our way back into their home and their beds. We were dead tired and lost. We would have been quite happy to sleep on the floor, but they found beds for us all. Howard and I shared a three-quarter bed but I was too tired to think about whose bed it was, or whether the Melbourne Truth would make something of it.

All The Pictures That Fit

In the morning, Howard said he would like to film the youngest of the adopted boys. This was a little Indian fellow about a year old. He was wearing nappies, thus marking him as the child of foreigners.

John set up the camera facing a broken-down wall by the house looking across empty fields towards a distant village. Howard asked the girl to bring her young brother over by the wall. John filmed as the boy stood forlornly alone by this picture of apparent devastation. The wall had tumbled down long before the cyclone. It wasn't so much a picture of the story, as a picture that fitted the story.

John set up the camera facing a broken-down wall by the house looking across empty fields towards a distant village. Howard asked the girl to bring her young brother over by the wall. John filmed as the boy stood forlornly alone by this picture of apparent devastation. The wall had tumbled down long before the cyclone. It wasn't so much a picture of the story, as a picture that fitted the story.

"Go inside," John suggested to the girl, and she obeyed.

The little fellow by the wall suddenly realised that he was surrounded by strangers. As the cameras rolled, he cried loudly and sadly.

This shot-that-fitted-the-story provided the concluding scene for the report when it was shown on television. It communicated the loneliness of a child who had lost his family and his home in the cyclone. That wasn't his story, mind you. But that was the story that we were telling. It was a true story. It just wasn't his story.

Do you still believe everything you see on television?

Second Attempt To Catch A Train

At around 8:30 we pedicabed to Chirala station which was nearer to the leper colony than Bapatla. We wondered why we hadn't come here the night before.

I went to the station master and asked him about the train.

"Can you tell me what time the Hyderabad-Madras express is coming through?"

"Oh, Sir," he replied deferentially, "we are not knowing. But if you are waiting on the station, it is coming."

Presuming this meant we should wait here for the train, we piled up our gear and prepared to pass the time of day. We played cards, listened to the daughter about life for a missionary kid at an English boarding school, and the crushing boredom of being a foreign teenager in Chirala.

Presuming this meant we should wait here for the train, we piled up our gear and prepared to pass the time of day. We played cards, listened to the daughter about life for a missionary kid at an English boarding school, and the crushing boredom of being a foreign teenager in Chirala.

The previous night's experience had made me anxious about Indian trains, so I decided to check regularly on progress.

At 9:30 I again asked the station master. "Can you tell me what time the Hyderabad-Madras express is coming through?"

"Oh, Sir," he replied deferentially, "we are not knowing. But if you are waiting on the station, it is coming."

I was to have this conversation about a dozen times during the day. Each time the same question. Each time the same answer.

"Can you tell me what time the Hyderabad-Madras express is coming through?"

"Oh, Sir, we are not knowing. But if you are waiting on the station, it is coming."

Meanwhile, the day passed slowly. A few trains came through and John filmed them. None was going our way.

Finally, at five I asked the station master again. This time, for some reason, I asked the question differently.

"Can you tell me what time the Hyderabad-Madras express stops here?"

"Oh, Sir," replied the station master with surprise, "it does not stop here."

The Empire To The Rescue

I was still processing this amazing fact a few minutes later when a British woman arrived in a Land Rover.

"I heard there were some foreigners here waiting for the train to Madras," she said, addressing me. Clearly, I was the alleged foreigner. "You can't catch it here, you know."

"Err, yes," I replied like a schoolboy trying to explain missing homework, "I just found that out."

"Come with me," she said and bundled us all into her Land Rover. It carried Oxfam decals on the doors. She was their local representative. She spoke with the tired confidence of someone who had been in India a long while and had seen precious little for it.

Within minutes we had returned to the scene of the previous night's crimes Bapatla station.

"The train comes in each night at around nine," she explained carefully. "Although it might be a bit later." This sounded familiar to us, of course.

"Let's go and meet the station master," she commanded, and we all followed like a line of goslings after Mother Goose.

The station master stood to attention and the lady from Oxfam gave a Joyce Grenfell-ish speech.

"Very important Australian journalists . . . extremely valuable photographic equipment . . . Need your very special service . . . Making a film for international television (really?) . . . friends of the Indian people . . . Need your very special service."

This went on for about five minutes while the station master stood at attention and nodded his understanding. She was magnificent. I almost started humming Land of Hope and Glory.

"This man," she said, pointing in my direction in a way that made me snap to attention too, "will be most grateful to you for your very special service. He would like to take your photograph and send you a copy in appreciation of your fine service."

I said that this was definitely what I had in mind. The station master smiled broadly and shyly, anticipating the honour of having his photo taken by this Internationally Important Photographer.

The station master took a huge ring of keys and we followed while his porters carried all our luggage to the First Class waiting room.

I took out my Nikon and took a series of photos of the station master at his desk. Naturally, I honoured my promise and sent him copies. He sent me a nice thank you letter and asked if I could get a job in Australia for his nephew.

The Oxfam lady disappeared in her Land Rover into the night. God had sent an angel. I doubt she found us entertaining.

Third Attempt To Catch A Train

When the train approached at around 9:30, the station master was true to his word. He carried a lamp with a red filter over the light. He positioned us on the platform at the place he wanted us to board. When the train arrived, he sent two men on board to clear out a cabin for us. I had no energy to consider the injustice of this, but then I had little frame of reference to do so. It seemed to me that we had a right to a sleeping berth, perhaps because we always slept on beds, unlike so many locals. Such arrogance is painful to recall.

Not until all our bags were on board, and we were all settled in place, did the station master withdraw the red filter and replace it with a green one. As the train pulled out, he stood to attention and saluted.

I slept the sleep of relief for the ten hours it took to trundle into Madras. We found our way back to our original hotel and were permitted to check in a day late. I called the office.

"Praise God," the Operations Director said. "We thought you were lost altogether. George arrived back yesterday without you, and he has been worried sick. He could not find you on the train at Bapatla."

He didn't have a station master with a red light. That was his problem.

Stealing A Woman's Memories

In the afternoon I went by the office to sort out what to do with the money I had left over from my friend's account. I couldn't take it with me. We discussed the matter in the lounge room of the director's house.

While waiting for the others to arrive I looked around the modest room with its plain furniture. It was lacking decoration, save for a couple of black figurines each about the size of my hand.

As Mrs Sojwal brought my tea, I attempted conversation.

"What are those figurines?" I asked.

She told me where they were from. "There are many dancers there. My husband and I visited there once."

"They are very lovely," I said. Actually they were quite plain and clearly had more value to her as reminders of a visit than any intrinsic value.

Today these figurines are in my own lounge room. Since I had expressed interest in them, Mrs Sojwal felt duty bound, within her culture, to give them to me. As I left after our meeting, she met me at the door with a small parcel wrapped in a sheet of newspaper.

"This is for you," she said quietly. "And your wife," she added.

I thanked her not knowing what she was giving me. These days, the figurines remind me of my own carelessness, and of an important lesson in cross-cultural communications.

Long Hair And Singapore

Getting flights out proved not too troublesome. And getting through customs with our film even less. Again, careful work by our Indian colleagues smoothed the way in advance.

The change in plans required an overnight stopover in Singapore. These days, such a diversion would be welcomed. In 1978, Singapore was going through one of its anti-decadence periods. Gum chewing and long hair were banned.

Unfortunately, what is de rigueur for sound technicians was anathema for Singaporean Immigration officials. Ian was given two choices. He could stay in the terminal until his flight out the next day. Or he could go and have a hair cut. Since he was being married within a few days, and didn't fancy explaining a severe hair cut to his bride, he opted for the rest in the terminal. These days, of course, the Singapore terminal is a mini-city. Living there for a day seems a pleasure. In 1978, the terminal was more utilitarian.

The report went to air in December. Willesee tagged it with an appeal for funds through World Vision. The Australian ran one of my pictures and a few paragraphs under my by-line. We raised $100,000 for the relief program that provided clothing, medicines, shelter and agricultural rehabilitation.

Next Chapter

Meanwhile, back at the hotel, the camera crew were already at work shooting local colour including the obligatory snake charmer in the hotel forecourt. There was no opportunity to see the rushes, and these shots never ended up in the report.

Meanwhile, back at the hotel, the camera crew were already at work shooting local colour including the obligatory snake charmer in the hotel forecourt. There was no opportunity to see the rushes, and these shots never ended up in the report. In India it was like a journey back to the '50s. The cars had different names, but they were Morris Minors and Austin Cambridges. I suppose some State run industry had bought the moulds from Austin-Morris and were stamping out these venerable machines in a market protected from imports. We were to discover that these vehicles had inherited all the unreliability of their forebears.

In India it was like a journey back to the '50s. The cars had different names, but they were Morris Minors and Austin Cambridges. I suppose some State run industry had bought the moulds from Austin-Morris and were stamping out these venerable machines in a market protected from imports. We were to discover that these vehicles had inherited all the unreliability of their forebears. Inside, young ladies in saris were crowded together in hot rooms. I thought it was intolerable. These people need more space. I was thinking. They need air-conditioning. They need a Coke machine.

Inside, young ladies in saris were crowded together in hot rooms. I thought it was intolerable. These people need more space. I was thinking. They need air-conditioning. They need a Coke machine. We stopped for lunch at a hospital run by an English missionary couple named Scott. Assuming they would serve up fish and chips, I was rather unprepared for my first taste of serious Indian curry. I could not eat even the first mouthful. It seemed my whole face had been hit with buckshot. My nose went numb, and all my teeth seemed to have separated from the jaw. Taking pity on my distress, they offered a banana, the perfect cure for curry. I remember thinking that it must have been a practical joke. No-one ate this for real, did they?!

We stopped for lunch at a hospital run by an English missionary couple named Scott. Assuming they would serve up fish and chips, I was rather unprepared for my first taste of serious Indian curry. I could not eat even the first mouthful. It seemed my whole face had been hit with buckshot. My nose went numb, and all my teeth seemed to have separated from the jaw. Taking pity on my distress, they offered a banana, the perfect cure for curry. I remember thinking that it must have been a practical joke. No-one ate this for real, did they?! So John climbed under the A40 and worked out what the problem was. Something to do with the diff, which he helped to repair. I guess, if you can fix a Bolex film camera, a motor car's differential seems pretty simple.

So John climbed under the A40 and worked out what the problem was. Something to do with the diff, which he helped to repair. I guess, if you can fix a Bolex film camera, a motor car's differential seems pretty simple.

In one place the whole village had rushed into a stone church building for shelter. Over a hundred people were crowded in when the wind pushed the walls over. A man and a young girl were the only ones to survive. They happened to be standing by the door as the building fell, Max Sennet-like, around them. All the others were crushed to death. When the winds died, these two pushed the door up and found their families quiet and still under the rubble.

In one place the whole village had rushed into a stone church building for shelter. Over a hundred people were crowded in when the wind pushed the walls over. A man and a young girl were the only ones to survive. They happened to be standing by the door as the building fell, Max Sennet-like, around them. All the others were crushed to death. When the winds died, these two pushed the door up and found their families quiet and still under the rubble. Time passed.

Time passed. John set up the camera facing a broken-down wall by the house looking across empty fields towards a distant village. Howard asked the girl to bring her young brother over by the wall. John filmed as the boy stood forlornly alone by this picture of apparent devastation. The wall had tumbled down long before the cyclone. It wasn't so much a picture of the story, as a picture that fitted the story.

John set up the camera facing a broken-down wall by the house looking across empty fields towards a distant village. Howard asked the girl to bring her young brother over by the wall. John filmed as the boy stood forlornly alone by this picture of apparent devastation. The wall had tumbled down long before the cyclone. It wasn't so much a picture of the story, as a picture that fitted the story. Presuming this meant we should wait here for the train, we piled up our gear and prepared to pass the time of day. We played cards, listened to the daughter about life for a missionary kid at an English boarding school, and the crushing boredom of being a foreign teenager in Chirala.

Presuming this meant we should wait here for the train, we piled up our gear and prepared to pass the time of day. We played cards, listened to the daughter about life for a missionary kid at an English boarding school, and the crushing boredom of being a foreign teenager in Chirala.